Chiropractic has had a colourful history since its invention in the 19th Century.

Chiropractic has had an extraordinary history, but the vehement response of its practitioners to criticisms of its claims is nothing if not human. These unwelcome aspects of human behaviour – a readiness to believe and a violent reaction to well-founded criticism – were recognised and categorised by Francis Bacon 400 years ago.

Chiropractic has been defined as “a system of treating bodily disorders by manipulation of the spine and other parts”.1 The Oxford English Dictionary gives a number of meanings for manipulation, including “The act of operating upon or managing persons or things with dexterity, especially with disparaging implications, unfair management or treatment”. Manipulate, among other meanings, is “to manage by dexterous contrivance or influence, especially to treat unfairly or insidiously for one’s own advantage”.

[Until 1818 English dictionaries gave only one meaning for manipulation: the method of digging for silver ore.]

The practice of chiropractic began in the US in 1885. It is one of a number of strange behaviours and belief systems which have had their origins in that country, including osteopathy, craniosacral manipulation, applied kinesiology, scientology, creationism science, Christian Science, and Mormon beliefs. It was in that country too that homeopathy received its greatest support after its invention in Europe. Why this should have happened is an interesting question. An American friend says that it springs from an overwhelming desire to avoid the perceived errors of Europe with its suppression of religious freedom.

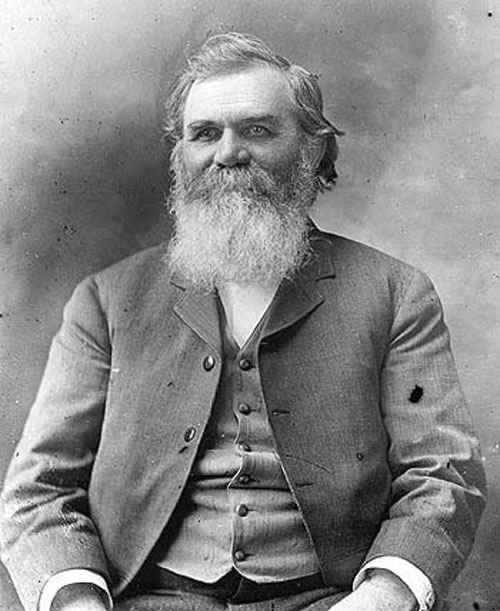

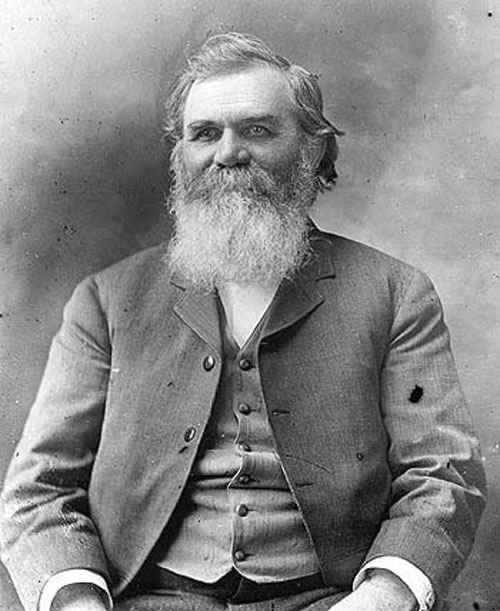

David Daniel Palmer was born in Ontario in 1845, and brought his family to the US where by 1865 they were living in Davenport, Iowa. He was a grocer, and a bee-keeper, and had a deep interest in spiritualism. He practised ‘magnetic healing’ and called himself ‘Doctor’. 2, 3, 4

He later said that the idea of chiropractic came to him as ‘received wisdom’ at a séance in 1885, from a certain Dr. Jim Atkinson, deceased at that time. Shortly after this, on 18 September, 1885, he treated a man who had been deaf for 17 years. He said: “I examined him and found a vertebra racked from its normal position – I racked it into position by using the spinous process as a lever, and soon the man could hear as before.” He went on: “There was nothing crude about this adjustment; it was specific, so much so that no chiropractor has equalled it”.

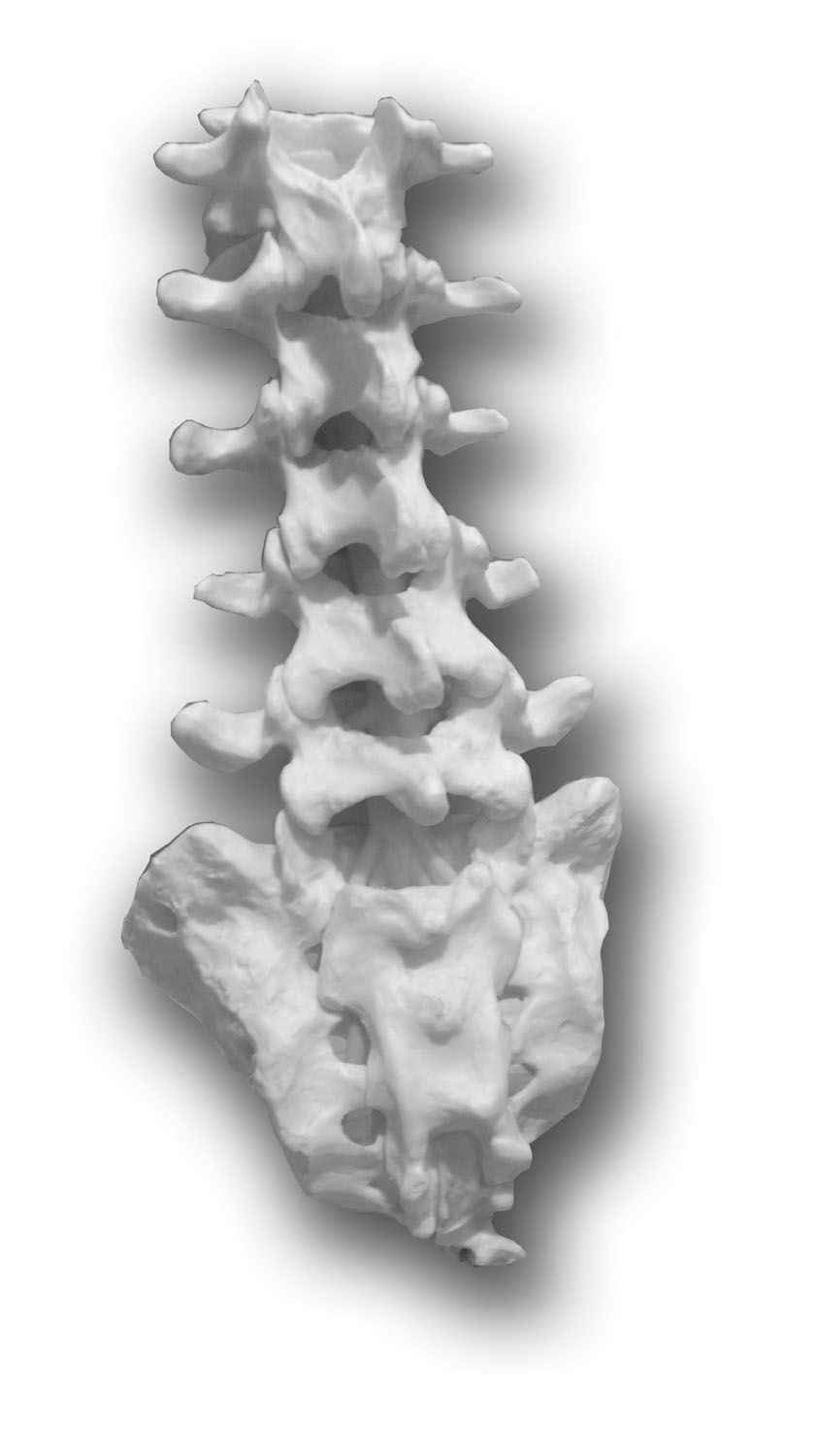

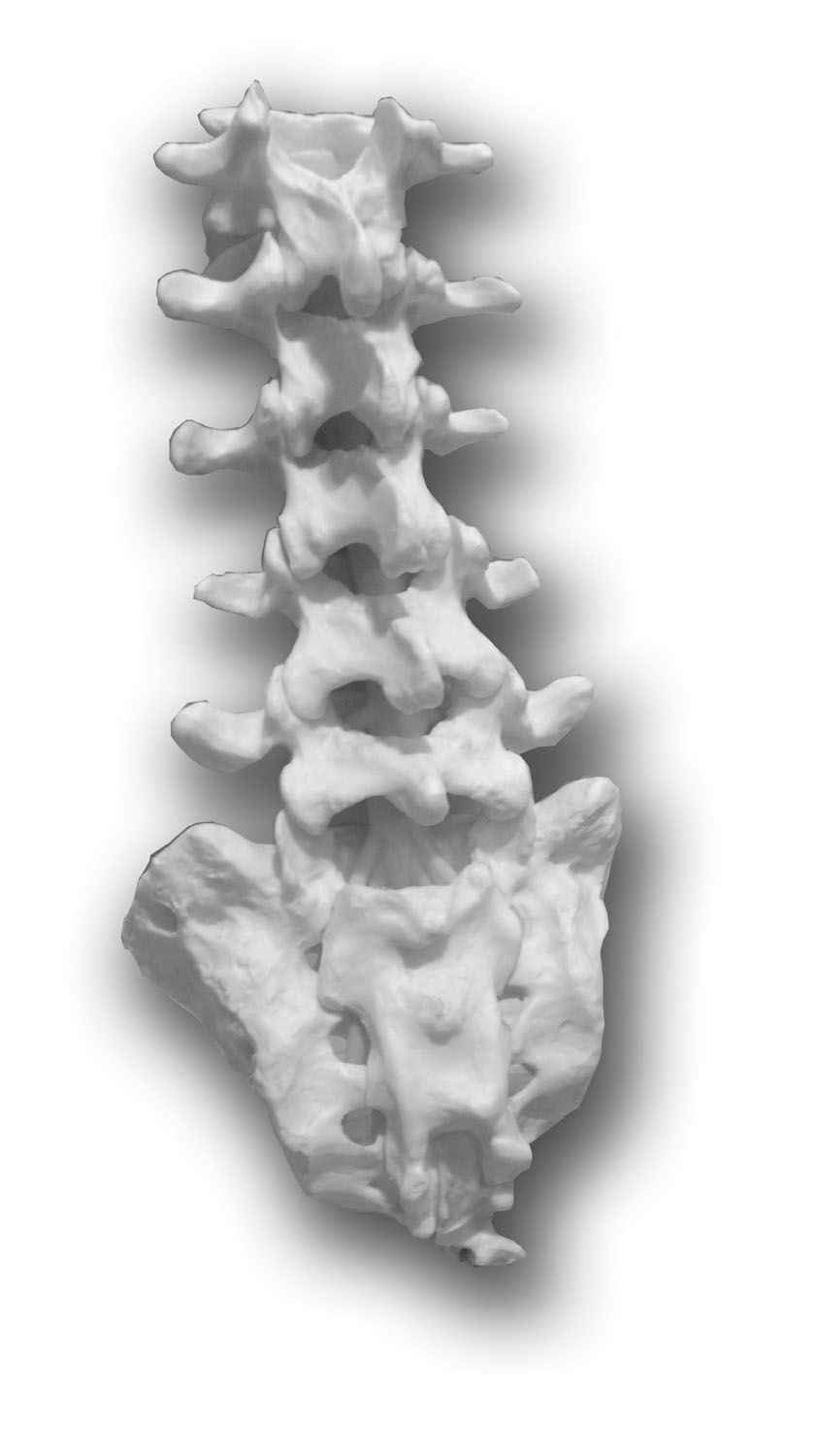

Palmer called the spinal irregularity he had found a “subluxation”, a term borrowed from orthodox medicine where it means a partial dislocation of a joint. Only chiropractors can find, feel, or see their patients’ abnormalities, which they proceed to correct.

Palmer decided there must be a single cause for all diseases: “I then began a systematic investigation for the cause of all diseases and have been amply rewarded.” He had a friend coin the word ‘chiropractic’ from the Greek ‘cheir’, hand, and ‘praxis’, action. He said that the free flow of the body’s ‘innate intelligence’ (or ‘psychic energy’) to all parts of the body was interrupted by spinal vertebral subluxations, and this was the cause of 95 percent of all illnesses.

He said: “I occupy in chiropractic a similar position to Mrs [Mary Baker] Eddy in Christian Science. Mrs Eddy claimed to receive her ideas from the other world and so do I. I am the fountainhead.”

Palmer was hugely successful. In 1897 he opened the ‘Palmer School of Care’ in Davenport. Admission was by payment of tuition fees and no other qualification. In 1905 it was renamed ‘The Palmer School of Chiropractic’ and it has gone on to occupy a large campus on what is now called Palmer’s Hill, in Davenport.

His son, Bartlett Joshua (‘BJ’), took over the business in 1906, while his father was in prison for practising osteopathy and medicine without a licence. DD and BJ fell out and DD opened a rival school.

By 6 August 1908, the US congress was considering a bill to regulate the practice of chiropractic and to licence chiropractors.

David Daniel Palmer died in 1916 a short while after being run over by BJ in an automobile. The death certificate said ‘typhoid fever’.

Bartlett Joshua Palmer made a fortune, and promoted chiropractic in Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom. He stressed salesmanship as he taught, and his classrooms were decorated with such slogans as:

“The world is your cow, but you must do the milking”

and

“Early to bed and early to rise, work like hell and advertise”.

BJ marketed a patented machine called the Neurocalometer which he said could detect subluxations, whether or not the patient had symptoms. It is still sold today as the Nervoscope and costs about $US799.

BJ founded a radio station, WOC (Wonders of Chiropractic) in 1924.

In 1926, HJ Jones in Healing by Manipulation stated there were more than 8000 chiropractors in the US and Canada.

BJ died a multimillionaire in 1961.

This story is one of extremely successful entrepreneurship in the best tradition of American showmanship. It has nothing to do with science, and a lot to do with evangelical know-how.

In 2007 there were 19 colleges of chiropractic in the US, two in the UK, at least one in Australia and one in New Zealand.

Repeated examinations of x-rays, MRI scans and autopsy material have failed to show any evidence for existence of the ‘subluxation complex’. The American Association of Chiropractic Colleges states that “the subluxations are evaluated, diagnosed, and managed through the use of chiropractic procedures”.

Because of Palmer’s initial dogma, many chiropractors reject the role of infectious agents in disease and hence deny the value of vaccination.5 Chiropractic neck manipulation is associated with an increased risk of vertebro- basilar vessel damage.6 Chiropractors insist on spine x- rays even when the risk of unnecessary exposure to radiation is raised, and this despite the absence of x- ray changes consistent with a ‘subluxation’.

A careful examination of all the scientific evidence7 has resulted in the conclusion that chiropractic offers some help for low back pain but otherwise has no more effect than that of a placebo for any other complaint.

In 1999 an American chiropractor, Samuel Homola, published Inside Chiropractic: a Patient’s Guide8. He supported manipulation for back pain, but rejected what he described as chiropractic dogma. He confirmed that the chiropractic profession had little tolerance of dissent.

“Its nonsense remains unchallenged by its leaders, and has not been denounced in its journals. Although progress has been made, the profession still has one foot planted lightly in science, and the other firmly rooted in cultism.”

He was labelled a ‘heretic’ by his colleagues.

Some commentators divide chiropractors into ‘straight’ dogmatists and ‘mixers’ who will use some science.

Chiropractors and defense by legal action: the American Medical Association Saga

In the US, doctors encouraged the arrest of chiropractors for practising medicine without a licence. By 1940 it is said that 15,000 prosecutions had been brought. However 80 percent of these had failed, with the United Chiropractors’ Association, encouraged by BJ Palmer, giving financial support to the defendants.

The AMA Committee on Quackery lobbied in 1963 to have chiropractors relegated to a non- medical status. The committee argued that chiropractic should not be recognised by the US Office of Education, citing the lack of scientific evidence, the denial of germ theory, the claim to be able to treat 95 percent of all diseases, and the use of the ‘E- meter’.

In 1976 the Chiropractors’ Association, having become aware of further action planned by the AMA, brought a suit against the association on the grounds that it planned to limit chiropractors’ practice, and this was in breach of anti- trust legislation as it was anti-competitive.

In 1987 the Court found in favour of the chiropractors, and an appeal by the AMA in 1990 failed.

The chiropractors had shifted the issue from science to rights of commercial practice. This was totally in keeping with their history of astute business acumen – and lack of scientific evidence.

The 1978 NZ Royal Commission of Inquiry into Chiropractic

In a context of legal and political mechanisms, the NZ Chiropractors’ Association with its supporters, and the NZ Medical Association and its supporters, battled for and against official recognition of chiropractic as a national health resource, and the access of its practitioners to the rewards from the Accident Compensation scheme.

The chiropractors bolstered their position with hundreds of letters to the commission from satisfied customers, and the NZMA responded by scathing and dismissive comments as to the worth of such letters, and by decrying the lack of science in the practice of chiropractic.

Kevin Dew9 suggests that the result was a negotiated settlement exchanging a proposal by chiropractors to restrict their practice to musculoskeletal conditions, in return for official Government recognition, and the addition of chiropractic to New Zealand’s health resources.

The controversy was resolved without any resolution as to the scientific validity of the claims of chiropractic. It was thought there were only 100 chiropractors in New Zealand at that time.

Recent publications6show that the majority of chiropractors in the English- speaking world continue to make claims for their treatment which extend well beyond the realm of musculo- skeletal disorders.

There were 391 chiropractors advertising in the Yellow Pages in New Zealand in August, 2010.

Simon Singh and the British Chiropractors’ Association

In 2008, Simon Singh and Edzard Ernst published a book called Trick or Treatment.7

On 19 April 2008, Singh wrote an article in The Guardian, pursuing the topic canvassed in the book, that chiropractic was alternative medicine and there was no evidence for any effect except on lower back pain.

“The British Chiropractors’ Association claims that their members can help treat children with colic, sleeping and feeding problems, frequent ear infections and prolonged crying even though there is not a jot of evidence. This organisation is the respectable face of the chiropractic profession, yet it happily promotes bogus treatments”.

The BCA quickly sued him for libel, and on 7 May 2009 the court handed down a verdict in favour of the chiropractors.

Meanwhile in New Zealand

On 25 July 2008, the NZ Medical Journal published a paper by Andrew Gilbey reporting evidence that some chiropractors in NZ were using the title ‘Doctor’ in a manner which could mislead the public. In the same issue an editorial by David Colquhoun appeared, critical of chiropractic, and the qualifications of its practitioners. He wrote:

“For most forms of alternative medicine, including chiropractic and acupuncture the evidence is now in. There is now better reason than ever before to believe that they are mostly elaborate placebos, and at best are no better than conventional treatment.”

In the next issue of the NZMJ the editor published a letter from a lawyer, Paul Radich, representing the NZ Chiropractors’ Association, threatening legal action under the NZ Defamation Act, against the journal, Gilbey, and Colquhoun. The letter demanded apologies from all parties, and outlined the financial penalties for all.10 The tone was intimidatory.

In his comments about the position of the NZMJ as a scientific publication, the editor, Frank Frizelle, invited the chiropractors to an evidence- based debate with these words: “Let’s hear your evidence, not your legal muscle”.

The NZMJ published an invited response from the NZ College of Chiropractic in its next issue11 and I understand there has been no further correspondence from the lawyer (personal communication from the editor, NZMJ, September 2010).

Back to London

A month after the initial court procedure in London, Simon Singh announced his intention to appeal the finding in favour of the BCA.

On 1 April 2010 the Appeal Court handed down its verdict. The Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales, The Master of the Rolls, and Lord Justice Sedley stated that Singh(s comments were not libellous, and that they were matters of opinion backed by evidence. They went on to quote an American judge, Judge Easterbrook, now Chief Justice of the US 7th Circuit Court of Appeals.

In Underwager v Salter 22 Fed.3d 730 (1994):

“Plaintiffs cannot, by simply filing suit and crying ‘character assassination’ silence those who hold divergent views, no matter how adverse those views may be to the plaintiff’s interests. Scientific controversies must be settled by the methods of science, rather than by the methods of litigation. More papers, more discussion, and more satisfactory models – not larger awards of damages – mark the path toward superior understanding of the world around us.”

Back to New Zealand

As it happens, nine days after Singh’s appeal was upheld, Ernst and Gilbey authored a paper in the NZMJ: “Chiropractors’ Claims in the English-speaking World”.5 They examined 200 individual chiropractors’ websites and nine chiropractic association sites in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the UK and the US. They concluded:

“The majority of chiropractors and their associations in the English-speaking world seem to make claims which are not supported by sound evidence. We suggest the ubiquity of the unsubstantiated claims constitutes an ethical and public health issue.”

On 11 June 2010, Shaun Holt and Andrew Gilbey wrote a letter to the editor of the NZMJ12 drawing attention to the wider public scrutiny of chiropractic claims and nature following the success of Simon Singh’s appeal.

Francis Bacon and his ‘idols’

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) lived at a time when the new empiricism was disturbing the security and comfort taken in accepting the opinions of established authorities. He was a lawyer, a legal theorist, a judge, and a writer. He became Lord Chancellor, but was charged by Parliament with corruption, and having taken bribes from those appearing before him in court. He pleaded guilty and wrote: “I was the justest judge that was in England these fifty years, but it was the justest censure in Parliament these two hundred years.”13

Bacon wrote a series of ‘Axioms’ towards the end of his life. I would like to use some of these to examine aspects of human behaviour that the history of chiropractic reveals. It has been a considerable surprise to me to realise the prescience of this man.

He used the term ‘idols’ to list aspects of human behaviour.

Axiom 41: “The Idols of the Tribe”

These have their foundation in human nature itself.

“For it is a false assertion that the sense of man is the measure of things. On the contrary, all perceptions, as well of the sense as of the mind, are according to the measure of the individual, and not according to the measure of the universe.”

We are all subject to our nature, and seek security and certainty, and believe the evidence of our eyes. If we get better after manipulation, then clearly the manipulation made us better. Emma Young says: “We are causal determinists – we assume that outcomes are caused by preceding events”.14

Axiom 42: “The Idols of the Cave”

These are the idols of the individual man, due to our own peculiar natures, our education, our own experiences, or to reading from authorities we admire. “The spirit of man is in fact a thing variable and full of perturbation”. If we are told by our parents or teachers that someone else is better after manipulation, then we will believe that it is a ‘true’ relationship.

Axiom 43: “The Idols of the Marketplace”

“Formed by the intercourse and association of men with each other. For it is by discourse that men associate, and words are imposed according to the apprehension of the common understanding. The ill and unfit choice of words wonderfully obstructs the understanding. Words plainly force and overrule the understanding, and throw all into confusion and lead men away into numberless empty controversies and idle fancies.”

The choice of the word ‘subluxation’ for example, to describe an undemonstrable change! Or the claim for the existence of ‘psychic energy’. A radio station extolling the “Wonders of Chiropractic” is a wonderful Idol of the marketplace.

To take legal action and gain the publicity which is sure to follow with extensive argument about the meaning of, for example, ‘happily’ has great appeal in the marketplace.

Axiom 44: “The Idols of the Theatre”

“Which have migrated into men’s minds from various dogmas, and the wrong laws of demonstration. All the received systems are but so many stage plays – many more plays of the same kind may yet be composed.”

How well aware of this human trait are all showmen and charlatans. The Palmers, father and son, exploited this behaviour. To claim that new knowledge has come from beyond the grave is wonderful ‘theatre’, full of drama and mystery. To maintain the dogma of the wonderful in the face of evidence to the contrary is so much easier than to examine the evidence.

All these human behaviours can be seen in the history of chiropractic, and in so many other catastrophes such as the anti- vaccination campaign, the Peter Ellis trial, the Cartwright affair, the anti- fluoridation campaign and so on and on.

The history of chiropractic, and the response of chiropractors to criticism about the absence of science in their beliefs, illustrate the profound insights of Francis Bacon about our nature. It is our nature which results in the persistence of the perverse, and which resists the truth.

The responses of those without objective evidence for their personal beliefs often include ad hominem attacks, threat of legal action and financial injury, professional ridicule, and public invective. All these are seen in the chiropractors’ responses.

References

- Collins’ Concise Dictionary of the English Language (1988).

- Shapiro, R 2009: Suckers: How Alternative Medicine Makes Fools of Us All. Vintage Press, London.

- Carroll, RT 2003: The Skeptics’ Dictionary; A Collection of Strange Beliefs, Amazing Deceptions and Dangerous Delusions. John Wiley & Sons, NJ.

- Goldacre, B 2008: Bad Science. Fourth Estate, London.

- Ernst, E; Gilbey, A 2010: NZMJ, 123(1312) 36-44.

- Ernst, E 2007: J. R. Soc. Med. 100(7) 330-338.

- Singh, S; Ernst, E. 2008: Trick or Treatment: Alternative Medicine on Trial. Transworld Publishers, London.

- Homola, S 1999: Inside Chiropractic: A Patient’s Guide.

- Dew, K 2000: Sociology of Health & Illness, 22(3) 310-330.

- Editorial, 2008: NZMJ, 121(1279) 16-18.

- Roughan, S 2008: NZMJ, 121 (1280)72-74.

- Gilbey, A 2010: NZMJ, 123(1316) 126-127.

- Hollander, J; Kermode, F 1973: Oxford Anthology of English Literature. OUP, London & New York.

- Young, E 2010: New Scientist 2720.