Having a basic knowledge of the principles of chemistry can help one evade the pitfalls of many pseudosciences – but it’s not infallible. This article is based on a presentation to the 2011 NZ Skeptics Conference.

2011 is the International Year of Chemistry and as such I have been involved in a number of activities to celebrate the many contributions chemistry has made to our world. It has also been a time of reflection, during which I have asked myself, can an understanding of chemistry act as an antidote to pseudoscientific thinking? But first let us start with a definition of what chemistry is.

Chemistry is the study of matter, where matter is the material in our universe which both has mass and occupies space. Matter includes all solids, liquids and gases, and chemistry explores not only the properties and composition of matter but also how it behaves and interacts. Therefore chemists also have to understand how matter and energy interact.

While in theory chemistry can be described as an isolated discipline, in its practice and application it often contributes to, and is supported by, other scientific disciplines including biology (pharmacology, molecular biology) and physics (materials science, astrochemistry).

Core Chemical Concepts

At the heart of chemistry are some central concepts which form the foundation of this discipline. Let us examine some of these.

1) Matter is made up of atoms

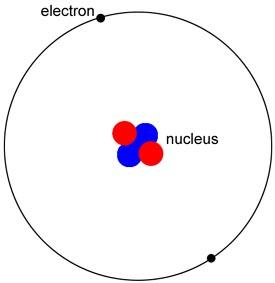

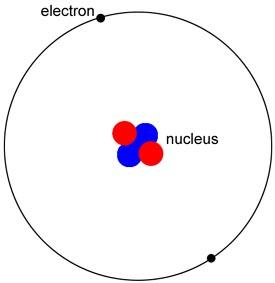

The most basic structural unit in chemistry is the atom. The atom itself is made up of a nucleus containing particles called protons and neutrons, around which smaller particles called electrons orbit.

2) Atoms with different numbers of protons give rise to the different elements

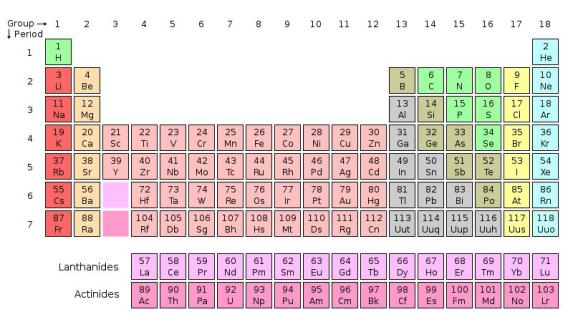

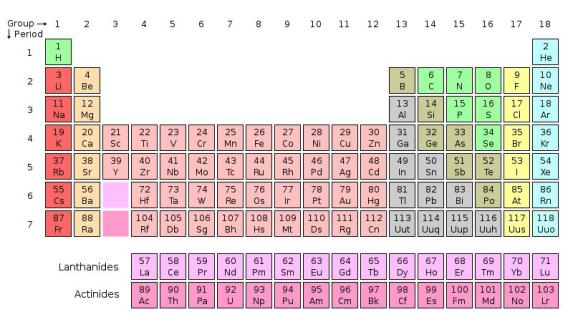

Atoms exist with different numbers of protons (neutrons and electrons). These different atoms afford the different chemical elements which are usually represented in the form of the periodic table (see diagram). Each element has different properties and is represented on the periodic table by a one or two- letter symbol. Ninety of the elements occur naturally and these elements can combine to form the fantastically diverse types of matter that make up our universe.

The atomic number (the number above each element) signifies the number of protons each atom has in its nucleus. You will see as you read across each row and then down the number of protons in the nucleus increases.

3) Atoms are really, really small

Atoms are so incredibly small that it can be hard to visualise how very small they are. For example, our lungs hold approximately 1,000,000,000,000, 000,000,000,000 gas atoms, while a grain of sand contains approximately 100,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 atoms.

4) Matter cannot be created or destroyed, it can however be rearranged

All of the atoms in existence were created billions of years ago in the heart of stars early in the formation of the universe. I find this an extraordinary concept – that the atoms which make up our bodies have existed for billions of years during which time some of them may have formed part of the last Tyrannosaurus rex, the first flowering plant, or occupied the bodies of various historical figures. Carl Sagan puts this more eloquently and succinctly when he explains that “we are made of star stuff.”

5)Atoms combine to form molecules

The true diversity of the matter in our universe comes from the ability of atoms to combine to form molecules. Molecules can be simple, for example water, which is made up of one oxygen atom and two hydrogen atoms, or complex, such as DNA, which can be made up of billions of atoms of the elements carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and phosphorus.

Molecules are also incredibly small – a single aspirin tablet contains approximately 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 molecules of the active ingredient, acetylsalicylic acid.

6) The shape of a molecule is key to its properties

The shapes of molecules have a fundamental effect on their properties. Water molecules, for example, have a V-shape which allows water to exist as a liquid at room temperature and to dissolve many different compounds. Without these fundamental properties, life as we know it would not have been able to evolve on Earth.

The shape of molecules is a key consideration in the development of new drugs. Many drugs work by interacting with specially shaped receptor or active sites in the body. To activate or deactivate these sites, a molecule of complementary shape must be able to fit into the site. And by making subtle changes to the shapes of such molecules it is possible to tune the effect of the drug molecule.

7) Matter moves

It may not be obvious to the naked eye or even under a microscope but all matter moves. In liquids such as water, the individual molecules move relative to each other, only fleetingly and temporarily interacting with other water molecules. This can be observed by adding a drop of food colouring to a still glass of water. The movement of the water molecules alone slowly mixes the colouring throughout the glass without any need for external agitation.

What do these concepts tell us about homeopathy?

Homeopathy was developed just over 200 years ago and is based on three principles:

a) that diseases can be treated by using substances that produce the same symptoms as the disease; b) that the greater a substance is diluted the more potent it becomes;and

c) that homeopathic solutions are ‘activated’ by physically striking them against a solid surface.

If one considers these principles against the core chemical concepts discussed so far they make little sense. How can less of a substance be more potent? How could the variable striking of water solutions have any effect on water molecules which are already in motion relative to each other, and which are therefore unable to form any collective memory of an active substance? For homeopathy to work, key chemical concepts which underlie and explain much of what we know about the physical world would have to be turned on their heads. Such a challenge to well-established chemical concepts would require extraordinary evidence.

To date, no such evidence has been provided by homeopaths. Instead, over the past 200 years, repeated attempts to prove that homeopathy works have demonstrated little more than the placebo effect and the human propensity for confirmation bias.

More Chemical Concepts

8) The Earth is a closed system in terms of mass

Apart from the launch of the occasional deep space probe, the loss of helium into space, or the addition of the occasional meteor, the Earth retains a constant mass. Thus, our physical resources are limited.

9) Matter is continuously recycled

Although we have a limited resource in terms of matter, this matter is continuously recycled as these ancient and indestructible atoms are converted from one chemical compound to another. For example, the carbon in coal when burnt is converted to carbon dioxide which may then be converted by plants into sugars. Such recycling occurs for many elements, particularly in the biosphere of our planet.

10) Chemical compounds can store and release energy

Some chemical compounds are rich in energy and this energy can be released to produce energy-poor compounds. For example, when we burn coal or oil we release energy and produce energy-poor carbon dioxide, or when we consume sugars we use the energy released in our bodies and again produce carbon dioxide. This carbon dioxide can be recycled through photosynthesis in plants to produce more sugars and other energy rich compounds for food. The same is not possible for coal or oil, and as such these are limited resources.

11) Systems are in equilibrium

The systems by which matter is continually recycled are very complex and interrelated. Such complex systems are usually in equilibrium – this means that if we change one variable the system will adjust itself to compensate. For example, as the amount of carbon dioxide has increased in our atmosphere, some of it has been removed by dissolving in the oceans.

The idea of system equilibrium is used by some to claim that an increase in carbon dioxide concentrations in our atmosphere is harmless as the system can rebalance itself. This is potentially dangerous thinking. Most systems, particularly complex ones, can only buffer a certain amount of change, beyond which the system may undergo significant change as it attempts to rebalance itself. Such changes would not necessarily be conducive to human life.

What do these concepts tell us about our environment?

Fossil fuels are a non-sustainable source of energy that also release pollutants and increase carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere. Humanity would be better served developing alternative sources of energy which harness the power of the sun more directly, for example, through solar panels, hydroelectricity, wind turbines or biofuels. More attention needs to be paid to the effects of increasing carbon dioxide levels in our atmosphere, and its effect on the equilibrium of the Earth’s biosphere.

Chemophobia – Causes and Consequences

There are millions of different chemical compounds in existence and chemists use a standardised naming system in order to better catalogue and compare these fascinating compounds. Unfortunately, amongst non-chemists this chemical jargon can create concern and even fear. For example, most people when asked would turn down an offer to eat a mixture containing methylmethoxypyrazine, phenylacetaldehyde and b-tocopherol, at least until it is revealed that the aforementioned mixture is a chocolate bar, and all of the compounds are natural components of chocolate.

This caution or fear of the unknown is a natural instinct which has served human beings well throughout our evolution – allowing us to avoid poisonous foods and dangerous predators. However, in the modern world it can be used against us. Referring to compounds by their chemical names is a ploy used by various interest groups including alternative health gurus and anti-vaxers to try and create fear of mainstream medicines.

Furthermore, it has allowed the development of the myth of the ‘chemical-free’ product. To a chemist, the only thing that is chemical-free is a vacuum.

The term ‘chemical-free’ appears to be an invention of the marketing industry: an attempt to sell products by suggesting that if they contain only natural compounds they must be safe, healthy and/or environmentally friendly. This is, of course, very flawed reasoning. Nature produces a wide range of compounds that are toxic to humans. Tetrodotoxin from poorly prepared puffer fish, ricin from castor beans (used to assassinate a Bulgarian dissident in 1978), digitalis from foxgloves and arsenic in groundwater are all just as capable of knocking us off as any synthetic compound.

Indeed, when it comes to toxicity it is not whether something is natural or synthetic that is important. Rather it is the dose. Any substance is capable of being toxic. Consuming four litres of water in two hours can prove fatal, as can several hours’ exposure to a 100 percent oxygen atmosphere.

The idea that toxicity is dose-dependent is not new. In the 16th century the Swiss physician Paracelsus stated that “all things are poison, and nothing is without poison; only the dose permits something not to be poisonous.” However, it remains a concept that is not well understood today. Special interests groups have used this to create fear around issues such as water fluoridation, vaccines, and environmental issues. For example, when DDT started to be detected in the environment at part per million levels, the resulting knee-jerk withdrawal of DDT from the marketplace resulted in a resurgence of malaria in many vulnerable populations. Following the introduction of DDT in Sri Lanka, by 1963 the number of cases dropped to 17. A few years after DDT use was banned, the number of cases increased to 2.5 million cases in 1968 and 1969.

Another consequence of chemophobia, is that it can encourage people to embrace ‘alternative’ treatments, such as homeopathy. An example of the terrible consequences of such erroneous thinking was the death of Gloria Thomas, aged nine months, in Australia in 2002, when her homeopath father refused to treat her eczema with conventional medicine. Instead, she was given homeopathic remedies until she died of septicaemia and malnutrition.

Absurd Chemical Therapies

One of the incredible hypocrisies of some alternative medicine practitioners is that they may also embrace absurd chemical therapies. Anti-vaxers who claim autistic children are really suffering from mercury poisoning sometimes promote the use of chelation therapy. Chelation therapy involves the intravenous use of chemical agents which bind to heavy metals in the blood. It is an invasive technique which can also strip the blood of important metal ions such as calcium. Indeed, there are examples of patients who have died because too much calcium has been stripped from their blood.

Other alternative treatments have included ‘miracle mineral solution’ as a treatment for everything from Aids to Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Such wide-reaching claims are an immediate warning sign, as is the revelation that ‘miracle mineral solution’ is, in fact, a 28 percent solution of bleach! Dilute solutions of dimethylsulphoxide (DMSO), an industrial solvent, have similarly been promoted as a cure-all, supported by, of course, only vague anecdotal evidence.

When challenged, those peddling these absurd therapies will often cry ‘conspiracy’, and claim they are being victimised by the all-powerful pharmaceutical industry.

Consequences of not understanding chemistry

We live in a world where important public debates are becoming contaminated with non-science and nonsense. Knowledge of chemistry can help us identify and challenge some of the non-science and nonsense when exploring important issues such as climate change, environmental issues, water fluoridation and vaccination.

Is chemistry an antidote to pseudoscientific thinking?

At the beginning of this article I posed the question, “Is chemistry an antidote to pseudoscientific thinking?” And while I hopefully have demonstrated that knowledge of chemistry can help identifiy and challenge pseudoscientific thinking, I cannot claim that it, alone, is an antidote. I know this because there are those who despite a background in chemistry still embrace pseudoscientific beliefs. These include:

- David Rasnick – after training as a chemist and working in medicinal chemistry for 20 years Dr Rasnick became an Aids denialist and proponent of vitamin ‘therapies’.

- Kary Mullis, Nobel prize-winning biochemist, is an Aids denialist, a believer in astrology, and claims to have met an extraterrestrial disguised as a fluorescent raccoon.

- Lionel Milgrom, research chemist for 30 years, is now a practicing homeopath and prominent advocate of homeopathy.

The idea that those who have trained to an advanced level in chemistry (or any other science) can go on to embrace pseudoscience has always intrigued me. I’ve often wondered how such a transition could occur, and would suggest that perhaps one or more of the following factors may be involved:

1) Frustration with science

Progress in science is often slow and frustrating. The temptation to find an easier, albeit fallacy-based career may be appealing when faced with the many frustrations of laboratory work.

2) External bias

Religious and moral beliefs may introduce bias. For example, a number of Aids denialists are blatantly homophobic.

3) No understanding of the scientific method

While most scientists pick up the principles of the scientific method during their training, few that I am aware of are explicitly taught the scientific method.

4) Need for attention/notoriety

5) Financial motives

The peddling of pseudoscience can be quite lucrative, particularly when you can use academic qualifications to lend the appearance of legitimacy to one’s claims.

I suspect that in most cases, the embracing of pseudoscientific beliefs by scientists is a gradual process, where step by small step, they move away from the scientific method until eventually they find themselves no longer bound by its philosophy and rigour.

Conclusion

While an understanding of chemistry does not necessarily provide an antidote to pseudoscientific thinking, when coupled with the tools of rational thinking, it provides the skills to critically assess many areas where pseudoscientific beliefs persist including water fluoridation, environmental science, climate change, homeopathy and alternative medicines.

“Never let yourself be diverted by what you wish to believe, but look only and solely at what are the facts.” -Bertrand Russell