In NZ Skeptic 82, John Welch wrote that there was something about general practice which attracts an interest in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Is it acceptable for medical graduates with a science degree to be allowed to carry on in this manner? Should we amend the medical registration so they can’t? Is legislation needed to alter the culture-of doctors and society generally? This article is based on a presentation to the 2007 NZ Skeptics Conference.

Society confers upon the medical profession certain privileges, as it does upon lawyers, clerics, JPs and those entitled to issue warrant of fitness certificates. For the past 150 years or so the privileges enjoyed by doctors and those practising within the so-called orthodox health professions, have been granted and maintained upon the assumption that they undergo rigorous scientifically based education and maintain a scientific basis for their entire careers. The privileges can be quite rewarding in monetary and other terms.

We agree that the scope of such rewards implies an added burden of responsibility in understanding the nature of science and the requirements for application of scientific principles to clinical medicine. In modern society that is not as easy as it sounds. What follows is not a defence for doctors who may be failing to meet the assumed standards but rather our perceptions of why, so often, we doctors do as we do. We examine what we perceive to be a subculture which has always been present, but which may now be something of an epiculture.

For several thousand years doctors under various guises functioned independently of governments but not independently of the ruling classes. Various forms of Robin Hood-style financing kept the system going. Science, which essentially disproves current dogma progressively, infiltrated the healing arts. Medical education at university level in its present form dates back about 150 years. Paradoxically, junior doctors at Auckland City Hospital function much the way their forebears did at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary 150 years ago. Old-style apprenticeships still guide aspirants to the various specialties and subspecialties within medicine. In most of the western world, consultants split their time between private practice, which they regard as a no-go area for government, and their hospital duties which enable them to keep up to date with new ideas and with young people. Conversely, most full-time hospital doctors are employees of the government.

This pattern had its beginnings in the 1790s. The industrial revolution brought social and demographic changes which had catastrophic effects on the health of the community. The politicians, perforce, had to react. Thus began the moves towards what we can loosely term socialised medicine. Third parties came into the doctor-patient relationship.

A crucial event occurred in 1938. Sensing the advance of socialised medicine ideas in Europe, the all-powerful surgeons of the American Medical Association sent a delegation to Europe which met with the surgeons of Nazi Germany, France and England. It was agreed that big insurance agencies, largely owned and controlled by the medical profession but attracting private finance, should be established immediately. The important corollary was that remuneration for the doctors would be on a procedural basis.

Patients would pay for a particular procedural process and not for the time spent in performing it. Such remains the basis for private practice throughout the western world and for much general practice. It is a crucial controlling factor on the way doctors practise and a powerful formative influence on the aspirations of young entrants to the profession. The net effect is that the bigger economic rewards occur outside and separately from the government. Possession of a particular technique, plus some entrepreneurial flair, is good for business.

There will always be some imbalance and mismatch of information between patients and their practitioners. So-called third parties have tried to intervene between patient and practitioner to modify the system. These third party ploys have largely failed, spectacularly in the case of US medicine. In what other industry would a cataract operation of brief duration secure a fee greater than that for key-hole surgery for gallbladder removal involving a much longer duration?

Over the last 50 years medical technology and basic medical science have advanced at the expected accelerating growth rates. What is not so obvious is the devastating effect this has had on general medical practice. A very powerful health-disease oriented industry now operates within the western world. The financial success of the doctors generally has been studied carefully by non-medically qualified people and a parallel or alternative medicine system has mushroomed. Its power is quite obvious in New Zealand when it is faced with threatening legislation based on calls for proven efficacy. The scientific concepts that knowledge is continually changing and must be continually reassessed, and that efficacy should be the basis for change of therapy and professional remuneration, play little part in the world of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM).

Checking a myth

About ten years after the first graduates emerged from the Auckland Medical School there was a widespread myth that Auckland students, having had more behavioural medicine in their undergraduate course, were much better at taking histories from, and establishing empathy with, patients. Conversely, Otago students were alleged to be much better at practical procedures.

One of us (JS) didn’t believe this and received a grant to compare the performance at hospital level of graduates from the two schools. The pervasiveness of the myth was fully confirmed by the consultants, matrons and hospital superintendents who still existed at the time, and by many of the former students themselves. However, I did not restrict my study to gaining the opinions of administrators, chief doctors and chief nurses. I went to telephone operators, the women in charge of the residences, laundries, kitchen staff, orderlies and charge nurses on the wards. I knew many of the Auckland graduates on an individual basis pretty well. What pained me deeply was learning that bright young people, both men and women, whom I had known fairly well as undergraduates and whom I regarded as sensitive, intelligent and obviously well fitted for medicine, had turned into arrogant, sometimes rude, aggressive, insensitive, awkward creatures who often were destructively disruptive of team functioning. Conversely, many of that group were highly successful in terms of acquisition of postgraduate diplomas and remunerated positions. I felt my own judgment had been severely challenged in terms of my starting opinion of these emerging graduates. I went back to Auckland with my tail between my legs but decided to analyse the situation further, knowing also that the myth was a myth.

Emerging pattern

A clear pattern emerged between the aberrant behaviour as I saw it of these young people and their attachments to clinical teams in the fifth and sixth years of their training. This clear-cut relationship involved role modelling, inspired somewhat by the personality of the emerging graduates themselves. More importantly, role models of the aberrant group demonstrating what I thought was unsatisfactory behaviour, had been adopted particularly from some surgical specialty teams led by powerful personalities who demonstrated essentially egotistical, flamboyant and at times outrageous behaviour, which was accompanied by affluence and considerable medico-political power.

Within North America and the British Commonwealth, and to a large extent in Europe, based on the leadership of a few doctors, patterns of medical profession behaviour have survived by resisting waves of political pressure from sociologists, politicians and economists. The great medical registration Acts of mid-nineteenth century Great Britain, are touted as wonderful examples of the altruism of the medical profession. But the transcripts of the Westminster proceedings and the antics of the medical profession at that time, particularly those of some prominent surgeons, reveal how the medical profession adroitly preserved its position. Conversely, the divide between general practitioners and emerging specialists was ensured. Nevertheless, a great deal was gained for the population generally, in terms of paving the way for more scientific application to the practice of medicine. In 1945, with the introduction of the NHS, the specialists or consultants in Great Britain again feathered their nest at a time when the whole framework of state-supported practice was changed. In the late 1990s matters came to a head when for the first time a general practitioner was made Chair of the Greater Medical Council of Westminster. Things have changed since then but, in our opinion, the essential reform steps have yet to be undertaken.

Answering John Welch

We have now set the ground for our first response to John Welch. No, it is not acceptable for medical graduates with science-based degrees to be allowed to carry on earning considerable sums from some forms of CAM without analysing or acknowledging what they are doing, and all practised with apparent conviction that something unique or specific is being proffered. In so doing they have abandoned science-to what extent depends upon one’s perspective.

If such practice is reasonably widespread, how has this come about? We would argue that the environment into which students are released and the power of particular personalities can override what teachers believe they have inculcated into the minds of their students. In turn this means that the teaching has not been powerful or sustained enough, to carry sufficient clout. In keeping with changes in wider society, students are becoming more demanding of Faculty. Students are demanding more facts and less waffle. ‘Facts’ are equated with ephemeral knowledge, itself a sacrosanct entity which is essential for passing various hurdles. ‘Waffle’ refers to sections of the curriculum devoted to community issues, public health, communication matters and so forth. We are not aware of any satisfactory studies to back our belief that students in general are not particularly interested in lectures on the nature of science or induction into Bayesian concepts to which they theoretically subscribe. We know that many students still believe it is the business of government and administrators to find the money and resources for them to exercise their particular forms of practice, and thus for them to expend those resources freely and independently of audit or censure.

What do patients want?

The concept is abroad amongst some students and younger doctors, that patients always require something tangible from a practitioner and their problems cannot be dismissed without some tangible transaction. Students in turn interpret this as the need for them to manipulate highly visible props for reinforcement of the placebo effect.

When general practitioner incomes fall, offering homeopathy or chelation for a fee becomes attractive, particularly within a culture wherein needs and expectations are being expressed increasingly by members of a public who are increasingly influenced by advertising, non-scientific articles and spurious claims.

CAM at Med School

In the Auckland School of Medicine there are brief sessions devoted to the topic of CAM. The general approach offers the students a broad brush introduction to principles in common forms of CAM, why these appeal to the public, how the efficacy could be judged, and some attention is paid to identifying potential interactions with orthodox medicine. The topic is introduced in Years 2 and 3, and reviewed in Year 5. Given the present situation we believe there is considerable scope for providing a more detailed history of CAM within the curriculum, including scientific criticisms thereof, together with reinforcement at other stages of the course, concerning the nature of the conflict between science and non-science, the role of the doctor’s personality and projection thereof, and what they are contributing to the therapeutic interaction. In the New Zealand Medical Journal of May 2007 Rosemary Wyber and Tony Egan set about elucidating the views and experiences of a group of general practitioners and a group of current junior doctors one or two years out from graduation. To quote: “… A poor relationship with medicine is thought to be an area of considerable unconscious influence of role models. This may contribute to the well documented decrease in idealism during student and early clinical years.”

In the same issue, Tim Wilkinson, the Associate Dean of Medical Education at the Christchurch School of Medicine & Health Sciences, drew attention to the importance of getting the learning environment right. He wrote: “If learning occurs first within an environment of trust and respect … good role modelling will mean effective learning will not be undermined.” This line of reasoning is further reinforced in the same journal by an article by Kathleen Callaghan, Graham Hunt and John Windsor from the University of Auckland. They draw attention to failure of medical training to provide time for exposition of the non-technical aspects of competency.

We agree with their conclusion that professional training programmes need to be radically revised. Professional competency needs redefinition. Such definition must be team-orientated. Attitudes and aptitudes

Of relevance to John Welch’s first question is an issue raised by Callaghan and her colleagues. “Should there be testing of relevant attitudes and aptitudes prior to selection for postgraduate training?” Again, should we select prior to undergraduate training for a wider array of attitudes and aptitudes which would then be integrated and progressively monitored throughout undergraduate training, to ensure a differentiated work force of doctors based on society’s needs? These authors suggest some fundamental questions should include, “What are the patient outcomes that society expects us to deliver?” And “What are the professional competencies required to ensure that these outcomes are achieved?”

Attitudes towards (and use of) CAM in New Zealand were also studied by Poynton and colleagues in the NZ Medical Journal (2006). They found that the number of general practitioners using complementary and alternative medical therapies had decreased but the number referring patients to the unorthodox system had increased. They called for increasing information on CAM to be included in medical education and for attention to earlier research.

A call for reform

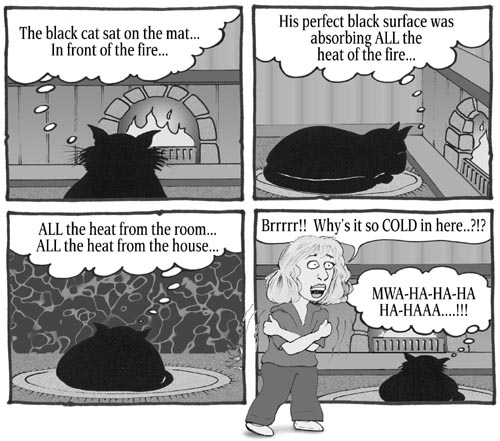

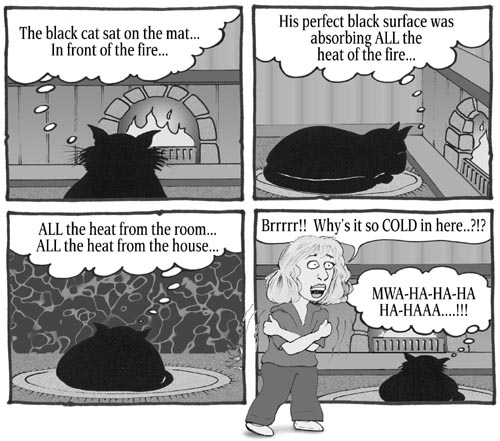

A Lancet editorial by Baker in 2005 stated that the time had come to explore the need for a major reform of medical institutions to make them fit to sustain professionalism and respond to the changing expectations of society. In so responding the medical profession and those who educate its entrants needed to have sound perspectives and the ability to challenge some of the false expectations within society. A key point in relation to false expectations is the utilisation of the placebo effect by both orthodox medicine and CAM. When properly handled, there is general recognition that the placebo effect is a boon to busy clinicians and their patients. However, such responses vary considerably between different diseases. Time heals a great deal. Some chronic diseases remit spontaneously. The first thing we educators need to do is to emphasise and demonstrate to students the natural history of disease. In so doing we need to place that in the context of the placebo effect and point out that such effects are notoriously fickle and may occur on one occasion and not on another within the same patient. Use of placebo effects varies across disciplines. We need to point out that large fees are not necessary for inducing a maximum placebo response-but time spent does require reasonable recompense nevertheless.

Scientific medicine and personal influence

Dr John Ellard, a prominent psychiatrist in Australia, has summed it all up in an article entitled, What can be learned from a curing of warts? To quote him: “… in most therapeutic situations there are two important aspects: scientific medicine, and the influence of one person on another. To ignore either is imprudent because the best outcome will be obtained only if both are considered … many remedies work quite well without a scientific basis. My argument is that one should strive for the best of both possible worlds-the greatest benefit from scientific medicine … and the greatest benefit from the healing power of concern for the person. Concern about the disease is not enough”. Moreover, adherence to medication or placebo was associated with lower mortality rates in a Canadian survey of 21 studies; patients’ psyche and personality are very much factors in determining outcomes.

The important point about Dr Ellard’s comment is that the mystique element is removed from the doctor-patient interaction associated with placebo effects. We believe there is no point in studying any mythical homeopathic mechanism, for instance, independent of the placebo effect. Observations of such therapies should be submitted to the same disciplines as evolving treatments in orthodox medicine. They should be controlled for consequences of the passage of time, that is of natural history, observations should be standardised and raw data made available for scrutiny by independent researchers at no extra cost to the subjects of such new (or old) treatments.

Social contracts

In reviewing social contracts much will be required in public education through public involvement and, to some extent at least, through lobbying and other manipulations of the legislature and the legal environment. Increasingly it will be in the interests of our nation as a whole, to review remuneration of time spent by health professionals and what balance should be set between expenditure within essentially a state-run system versus the proportion of national resources expended within an uncontrolled private sector. We believe some curbs will be required in future concerning irresponsible actions within the media, but unless the medical profession and public perceptions alter it will be impossible to develop a common culture and we will all fail together.

Within our present structure of cultures lie the medical students we select for the Otago and Auckland schools. The late Frank Haden pointed out at a previous Skeptics conference in Christchurch: “a doctor told us matter-of-factly that seven percent of the school’s 1997 fifth year students believed in creationism.” There is work to be done. We face an aggressive, burgeoning non-science or anti-science culture. Some of our students lie within awkward subcultures and some enter these after graduation. In finishing, we quote a 1995 Lancet editorial. “The intellectual strength of science lies in its essentially subversive character.” That same editorial quoted Freeman Dyson: “There is no such thing as a unique scientific vision … science is a mosaic of partial and conflicting visions. But there is one common element in these visions. The common element is rebellion against the restriction imposed by the locally prevailing culture.”

To this we can add the conclusion of a paper titled Health Delusions, written by Denis Dutton in 1988. “I am disturbed by a Listener editorial not long ago on the topic of alternative medicine which has gone so far as to call for government funding for fringe medical services. And this editorial ought not to be dismissed as an insignificant aberration: in the present user-pays climate of medical policy decisions it is possible that there will be increased pressure to turn our back on expensive, science-based medicine in favour of popular but worthless pseudoscientific placebos. I think it is imperative that health professionals throughout New Zealand work to resist such pressures. Our stretched public health resources must be directed towards valid, effective science-based care. Anything less will prove expensive and dangerous.”

List of references available from the editor.