NZ Skeptic issues 96, 97 and 98 contained articles presenting different viewpoints on the ‘Unfortunate Experiment’ at National Women’s Hospital and its aftermath. Wellington registered nurse and NZ Skeptics treasurer Michelle Coffey continues the discussion in this web-only special.

When I wrote my original article (NZ Skeptic 97), it was written with the intention that it could stand alone as a more thorough discussion of the findings of the Cartwright Report and later research. This was because there were a number of important issues raised as a result of the report which have been almost lost in the debate, many of them systemic ones. While I’m sure that readers interested enough can source the relevant material and judge for themselves, in Skeptic 98, Linda Bryder has responded and the statements made merit a response to clarify several points. I referenced the Bryder’s book for a complete review of the topic, but did not address it in the original article as while it does deal with aspects of the ‘Unfortunate Experiment’ the book ultimately fails to provide any complete assessment of the matter due to the book omitting to investigate key figures such as McIndoe or dealing with the health care system (in particular it’s politics) as opposed to social movements.

1. “There was no medical certainty about the proportion of cases of CIS…”

None of the references support the contention that there was no medical certainty about the proportion of CIS cases that would advance to invasion, and in any case proportion of cases isn’t the point – it’s whether CIS was considered to be a precursor of invasive cancer. This appears to be the case. In the Cartwright Report1 (p23) a compilation of studies was introduced into evidence giving figures that indicate over time, a significant proportion would progress to invasion.

The 1976 Editorial2 cited is discussing screening and states “The report faces up to the problems which still cause fierce controversy – those of the natural progression and regression of early lesions, the discrepancy between total [CIS] cases and the combined number of number of clinical invasive cases, and the incidence and mortality rates.” The Walden Report3 it is referring to states unequivocally that “The significance of [CIS] as a precursor of invasive disease has been recognised for more than 3 decades. Several series of patients, followed for months or years, have demonstrated progression from [CIS] to invasive disease at rates ranging from 25 to 70%.” The issue of where earlier dysplastic changes fit appears to be where any “controversy” laid rather than the concept of progression from pre-invasive lesion to invasion. The report placed these earlier changes a decade or so prior to invasive disease as a precursor state stating “the concept that progressive degrees of cervical dysplasia are part of the natural history of neoplastic disease of the cervix now seems firm.” This is relevant to developing a screening programme given that there is a window of many years in which the condition could be detected and treated. Ostor4 in his statement “The ultimate fate of patients with CIN is the most controversial issue facing investigators interested in cervical neoplasia.” is discussing similar issues to that discussed in the Walden report which is relevant in terms of assessing the relevance of findings and being able to predict the behaviour of these ‘atypias’. Most studies ended at the point of CIS. Ostor looked at not only progression to invasion but the likelihood of regression, persistence and progression to CIN3 (11% in the case of CIN1) with the conclusion that the probability of invasion increases with severity of dysplasia, but there is potential for regression which reflects on therapy.

One man’s dysplasia is another man’s carcinoma #40;notably without insertions to influence the reader to place a particular meaning on it) is a statement that crops up frequently. One issue is the correlation between cytology and histological confirmation, while this wasn’t perfect it was generally agreed that smears could reliably indicate an existing lesion. Histological confirmation was required, but there could be a lack of agreement between pathologists and laboratories on the histological criteria meaning that the precise differentiation between dysplasia and CIS varied. These uncertainties don’t seem to have impacted on the confidence of pathologists regarding screening for cervical malignancies and grading of a lesion was seen by surgical pathologists as more a statement of probability of progression which had limited applicability in clinical management as noted in Löwy’s history5. The precise definition didn’t matter as much as understanding that it was the same disease that was being managed. This is nothing other than a fairly typical debate as biology and medicine rarely, if ever, give certainties.

1. ” Coffey cites 1958 ” official policy… to show this.”

It’s important to note for clarity that there could be variation in policies in other areas but what is more critical in this case was policy at NWH, the hospital where Green practised which set the standard of care. Policies at NWH evolved over a period of time. In 1955 the formation of a cancer team to which all cases of carcinoma of the cervix were to be referred to for treatment was unanimously supported. Over the next ten years, policies regarding the diagnosis and treatment of CIS and invasive cancer were regularly reviewed. This wasn’t just agreed to at a meeting of “…only nine senior consultants…”the decision was made a formal meeting of the Hospital Medical Committee, with a majority which indicates that the committee was happy with the level of evidence for the policy. The clear majority and evolving policy don’t seem to fit too well with the narrative that there was considerable medical uncertainty and controversy about CIS and its progression.

2. “Professor Barbara Heslop explained this more appropriately…”

Heslop’s6 article is one to which I referred to in writing my article as I found some aspects of it informative. However, it is based in the opinions of the author so it’s unsafe to use this article to make certain statements about Green. Heslop considers that Green was doing research but seeks to place this in context stating “Herb Green aimed to ‘prove’ his hypothesis by carefully observing that dysplasia did not lead to cancer…Unfortunately, the proposed methodology was equally appropriate for showing dysplasia did lead to cancer. Paradoxically, and I am sure unintentionally, he ended up demonstrating…more convincingly than had been done before, the transition of dysplasia to cancer.” It was demonstrable that Green considered his work as a study initiated to test a theory and his 1974 paper said (p65) “This…represents the nearest approach yet to the classical method of deciding such an issue as the change or not of a disease from one state to another – the randomised controlled trial. It has not been randomised and it is not well controlled but it has at least been prospective…”

While Baker may have had the presumption that the therapeutic relationship would predominate, little suggests this happening in the case of Green. Whether he knew about such things as falsifiability, Green set out to prove his ‘dormant cancer’ idea despite indications early on that following such patients was unsafe (such as three cases of invasive disease in patients followed with positive cytology occurring by 1969). If the therapeutic relationship was predominant, those cases should have prompted reconsideration of the hypothesis; instead they were reclassified and removed from the study.

3. The 1966 management protocol was to “extend” conservative treatment…”

What seems to be being said here is that under 35 doesn’t mean that, but that it means older patients can be included as well. It should mean what it says as this was a safeguard intended to protect patients which Green then breached. When aging occurs, physiological changes mean it is more difficult to view areas of abnormality and Green and his colleagues were aware of this and the additional risks. The report (p37) stated “As a woman gets older, the squamocolumnar junction is more likely to lie in the endocervical canal and therefore be invisible to the colposcopist.” This means that it can’t be determined whether lesions extending further are suspicious and it was impossible to get a sample without a cone biopsy. Older women were more likely to have unsuspected invasive carcinoma. The use of words like treat is misleading as the intention was not to extend conservative treatment, but to monitor women with positive cytology to fulfil the aim of the proposal. As an example the proposal stipulated punch biopsies and used the word treat and treated (p 21 “four have been treated by punch biopsy alone.”) however this was regarded as a diagnostic procedure. The only way a punch biopsy could be a ‘treatment’ is if somehow by accident or design, the biopsy managed to obliterate a small lesion.

4. “Coffey presents this as a negative outcome, as if it was unnecessary outcome for the women.”

It was. There is a difference between ongoing monitoring which often can be done at primary care level and repeated attendances at a hospital over many years for multiple tests and interventions. Patient 4M (p44) was first admitted in 1970 with abnormal smears. In between 1970 and 1983 she had 38 appointments and six biopsies (wedge, ring, cone, surface) were performed with two occasions being histologically incomplete. A review of patient notes (p42) showed many women had more than one cone biopsy and in some cases up to six. Testimony showed that doing this more than twice was not considered unless under exceptional circumstances and doing this procedure could have effects such as stenosis or haemorrhage and make later evaluation difficult. Bonham testified that this was a dangerous practice and with the third or fourth conisation, it was probably a greater risk than hysterectomy.

Nothing in medicine is benign, and there are obligations to treat patients ethically. This includes minimising as far as possible unnecessary medical procedures as there are a number of risks entailed every time intervention is made. In a condition as treatable as CIS that could have been simply excised that means that over a period of time many women had a number of procedures that were unnecessary and posed excess risk to them that still left them with positive cytology resulting in risk of progression with its own complications. The associated disruption, pain and discomfort of these multiple interventions shouldn’t be trivialised.

5. Regarding the infant vaginal swabs, a press release by Judge Cartwright’s counsel stated “Mothers were told of the tests.”

Any kind of consent would have sufficed. Judge Cartwright stated (p141) “… there was no provision made to comply with the fundamental requirement that children are not included in research with the consent of their guardians.” This was not a test but a trial and was non-therapeutic research that held no benefit for the infant. Green quickly realised after 200 babies had undergone the procedure that it was a waste of time and lost interest in the study without communicating this to the nursing staff leading to over 2000 babies being subjected to an unnecessary and potentially harmful vaginal vault smear for the purposes of research without the consent of their parent or guardian.

With randomisation of Green’s 1972 “R series” radiotherapy and hysterectomy trial it is difficult to see that it conformed to international practice. Randomisation is aimed at preventing systematic differences between groups and preventing bias but in this case, the selection criteria were made in advance but there was no allocation of patients prior to anaesthesia, grading and decision on surgical treatment so no concealment. Enrolment could have been influenced by biases such as the need to enrol sufficient patients into the study along with the potential for further bias to be added with the use of coin tossing. The patients were not given any opportunity to consent, and were mislead about the treatment decision. Testimony on p170 states “Dr Green and myself and others discussed this question of informing women in the trial about it when it was initiated in 1972. We decided in the end not to tell patients about the trial. We told them they would be examined under anaesthetic when the most appropriate mode of treatment would be decided and then we would proceed accordingly.”

I can contrast this lack of any kind of consent from the parents or “R series” patients with the oral consent obtained by Sir Liley for his intra-uterine infusions where he sufficiently informed the patient of the possible risks and that the treatment was experimental. His case study published in 19637 states “the patient and her husband were an intelligent couple, and the prognosis for the foetus, the possibility and uncertainty of intrauterine transfusion, and the potential hazards to the mother were fully explained to and discussed with them.” This was not the case with Green and his research projects, as no real attempt was made to provide any kind of informed consent.

6. “Despite writing this, Coffey herself makes it clear that the two groups…had nothing to do with the two groups whose records Green analysed.”

This is an assertion and no reason is given as to why you state this. As such, there is nothing there to counter other than to say they had everything to do with those groups. McIndoe et al8 was retrospective while Green’s research was prospective, which made a difference in how the study was conducted but they were measuring the same thing as Green’s 1974 paper (p65) describes: “This series of 750 cases of in situ cervical cancer, and the following of 96 of them with positive cytology for at least two years…” The McIndoe paper was also a comparison of two groups of women, one with normal follow-up cytology and one without and was the final paper that Green never wrote that completed follow-up on the patients that were the subjects of his study. In my discussion, I highlighted the summary in the paper of patients who were included in the punch biopsy special series and that alone should make it clear the relationship between the “special series” and the study. I’m sure if Green could have asserted the same he would have, but couldn’t. The report didn’t rest on this paper alone but reviewed 1200 patient files and 226 were used as exhibits.

7. “Cartwright accepted this as “accurately reflect[ing] the findings of the 1984 McIndoe paper.”

Except Judge Cartwright did not. This is selective quotation that distorts the statements in the report and falls short of what you would expect from an historian whom you would expect to take care to fairly represent the context and statements in documents. The statement is from Ch4 “Expressions of Concern” where the article is addressed as it was the subject of public comment and had prompted the Hospital Board to request an inquiry. This put the article under scrutiny and criticism by some witnesses. Under the title “Was the magazine article accurate?” It is stated that the manuscript was submitted and editorial changes explained but there were some errors in the article that was finally published. This section states:

1.Significant editorial changes: The matter of accuracy was raised firstly by the authors themselves. In her evidence Sandra Coney drew attention to two editing changes which she considered substantially altered the meaning of sentences in the magazine article.

a. “Twelve of the total number of women had died from invasive cancer as had four, or 0.5%, of the group-one women, and eight, or 6% of the group-two women who had limited or no treatment.”

In the original manuscript the authors had written: “Twelve of the total number of women died from invasive carcinoma. Four (0.5%) of the Group-one women, and eight (6%) of the Group-two women who had limited or no treatment. Thus women in the limited treatment group were twelve times more likely to die as the fully treated group.”

I accept that the unedited material more accurately reflects the findings of the 1984 McIndoe paper. The edited version is not accurate.

It’s clear when looked in context that the statement was sourced from the original manuscript of the article and those words cannot be attributed to Cartwright. Cartwright is accepting that the original manuscript more accurately reflected the findings of the paper and is being misquoted to say something else. It is of note that in Bryder9 p33 that this statement is used to say “Cartwright too suggested differential treatment. In her report she quoted Coney and Bunkle’s statement that: ‘Twelve of the total number of women died from invasive carcinoma… [etc]” Cartwright accepted that this accurately reflected the findings of the 1984 McIndoe paper.” This statement is again used misleading to say something other than what it actually says and is being used inconsistently.

8.“How had they “returned to negative cytology”

McIndoe did not say treatment did not enter the study. The citation in Bryder used to reference this says only “The detailed management of patients is not under consideration in this paper…” The paper looks at the initial management and in some cases more detailed management of patients as Bryder would be aware. Here, it does become evident that there were differences, for instance in group 1 cone biopsies excision was incomplete in 24%, but in group 2, 74% were incomplete with the difference likely to be largely due to management where complete excision is not a necessity. The paper states “…any examination of the natural history of CIS of the cervix must depend on a representative, though incomplete, biopsy specimen on which to base the initial diagnosis. Thereafter, meticulous long-term follow-up of all patients using techniques such as clinical examination, cytology, and colposcopy, and if indicated biopsy, is required.” The paper detailed some limitations, such as small biopsies or possibly trauma eradicating lesions, or inadequate biopsies missing abnormalities. So in answer to that question, it was because initial management in group 1 patients either intentionally or unintentionally was adequate in treating the lesion and restoring them to negative cytology. Of this group only 0.7% had recurrence of CIS. In group 2, follow-up showed continuing positive cytology after initial management either by limited biopsy or incomplete treatment which was ideal for studying the natural history of CIS as set out in the 1966 proposal.

9. “Coffey refers to the 1986 paper…as critical of conservative treatment…”

This paper10 was only briefly mentioned before moving on with discussion of McIndoe et al as there was insufficient space to deal with it in detail. Here long term follow-up of vulvar carcinoma shows that of 31 patients managed by surgical excision, there were 4 recurrences and one developed a vulvar carcinoma 17 years later. 4 women managed only by biopsy progressed to invasion in 2-8 years and one additional patient managed with incomplete excision after a lengthy period of observation progressed to invasion. The paper demonstrated that untreated lesions have significant invasive potential. This approach was an extension of Green’s study of CIS of the cervix, and in this case a biopsy cannot be considered treatment at all. While the authors were advocating conservative treatment this was excision of the lesion not biopsies or incomplete excision.

10.“Would a modern gynaecologist agree with this assessment?”

The relevant sentence is presented as a statement, but it omits a significant portion of the sentence which is “This needs to be explained, as those figures strongly suggest the progression of CIS to invasion when it is and was a totally curable lesion.” Gynaecologists would accept the statement that CIS is a curable lesion which can be readily treated with a variety of local destructive methods with complete removal of the lesion and reversion to negative cytology which then prevents the risk of the lesion progressing. In the quoted statement McIndoe et al is referring to group 1 patients, whose cytology had returned to normal. It states “However, contrary to what would be expected, of the 139 group 1 patients with incomplete excision of the original lesion, only five (3.5%) later developed invasive carcinoma. Thus whether or not the lesion is completely excised does not appear to influence the possibility of invasion occurring subsequently.” In this case it didn’t, the rate of recurrence was unexpectedly small probably due to the initial intervention influencing the condition.

Treatment of a diagnosed lesion is then conflated with cervical cancer at a population level in asking for an explanation of why cervical cancer hasn’t been completely eliminated. In an ideal world this might be possible, but in the real world there are a number of difficulties to be faced in ensuring the entire population at risk is screened and treated if necessary. Green’s conclusion was that screening was not effective, however the conclusion was unjustified. The report discusses this on page 56 and crucially treatment needs to improve the prognosis as if subsequent cases are not adequately treated there is little value in screening in the first place. Also, if screening is done in low risk cases and high risk populations are missed, that means screening will be limited in being able to affect morbidity and mortality. In McIndoe et al, the age-standardised incidence of invasive carcinoma in group 2 was 1141/100,000 compared with 18.2/100,000 in the general population in 1975. This has since dropped considerably.

11. “As stated above, group 1 and group 2 had a similar range of treatments…”

My statements stand on this matter that “this ignores that while many women were treated with various procedures, there was evidence of continuing disease, demonstrating that the intervention was inadequate. This was not followed up, posing a high risk of development of invasive disease.” To prove that CIS is not a premalignant disease necessitated the area is sampled for diagnosis, but done in a way that left the lesion available for further study. In some cases there was no treatment, for instance the punch biopsy series which only used a diagnostic method. The criteria included that “the colpscopically-significant area is large enough not to be completely excised by the diagnostic punch biopsy.” The intention was to leave the lesion as undisturbed as possible. The use of cone biopsy is covered in q 5 and 9 as this could also be diagnostic. Of the hysterectomy series, only 4 out of 25 had the procedure for CIS so the procedure was done but not often specifically for CIS. Either way, women were left with positive cytology which put them at risk.

12. ” The methodology of the 2008 paper has been questioned by Sandercock and Burls…”

I would be embarrassed to cite this letter11 as an example of “questioning”. Every paper is flawed to a degree but this isn’t the right criticism to make. They cite a secondary source and claim this explains what they say is a problem with McIndoe et al – “He points out that, not only were the two group retrospectively divided on the basis of persistent abnormal cytology during follow-up and not prospectively as experimental groups for the comparison of different treatment strategies…” They misread the letter12 which does not appear to state anything regarding type of study and apparently draw from Overton’s misleading statement that “…Green and other senior NWH clinicians endorsed policy changes in dysplasia management. Younger women were to be continuously monitored, by repeat smears, colposcopy, lesser biopsies and appropriate more major surgery if evidence of early cancer.” which omits mention of Green’s role and his published studies. Sandercock and Burls then make an erroneous conclusion that McIndoe’s research should have been prospective and be following different treatments without realising that prospective research had already been done by Green. They cannot have read McIndoe et al despite citing the paper otherwise they would have seen the paper outlined the 1966 proposal. A few minutes reading would have shown the difference in between the statements which if they were honestly critiquing the study they should have checked.

Sandercock and Burls then claim a similar “problem” with McCredie et al even though they are aware it was retrospective. This might be correct to say for prospective studies that ask a question and look forward such as Green’s as this type of study should assess outcomes relative to interventions but retrospective studies are meant to pose a question and then look back. McIndoe et al looked at the question of outcomes for patients with CIS with the patient groups defined by presence of positive or negative cytology which categorised according to the risk they had persistent disease. McCredie13 takes this a step further with the approach being to look at the question of outcomes for patient groups classified by management that was adequate or inadequate. There is no problem with this approach; the problem lies with Sandercock and Burls.

13. “…It should be noted a study on outcomes cannot make such pronouncements…”

It can however tell a story, one that is further strengthened by understanding what the author is trying to achieve. Papers are meant to be considered in the light of all the evidence and that includes context. McCredie et al shows half the cancers in women initially managed with punch/wedge biopsy were diagnosed within 5 years of a finding of CIN3. It can be judged objectively there that merely doing a diagnostic procedure in patients with CIN3 leads to a high risk of developing cancer in a relatively short period of time, while the context shows up much more and shows the unethical nature of the original research which meant they were managed in that manner.

14. “Yet Green’s achievement was to encourage an openness to look at the evidence.”

Which story is it that is being referred to? The one where there is a controversy in medicine? If so, he wasn’t the spirited free-thinker he is being cast as. If it is the one where Green was the controversial one, willing to question modern medicine then the controversy wasn’t in medicine. If he is going to be cast as Galileo type of figure, persecuted for his heresy, the critical point is that Galileo was proven correct. So where are his papers? Even his supporters never present his papers to support their claims. Their resort is to complain about everything else.

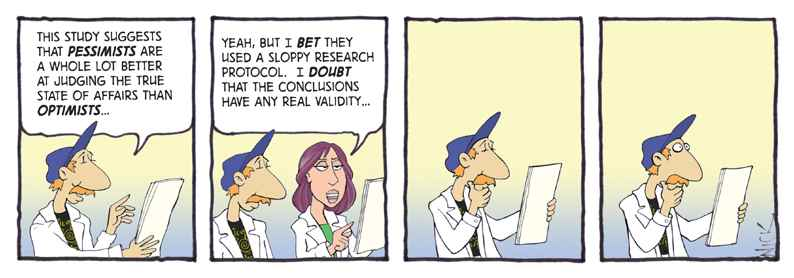

Green’s ‘achievement’ was the reverse. On p108 of the report, in an Auckland Star article in 1972 it was reported that “Professor Green asserted that a woman with a positive cervical smear showing what is called [CIS] is no more likely to develop invasive or malignant cancer of the cervix than any other woman of the same age. In other words, in situ cancer is not a forerunner of invasive cancer, and the smear test is over-rated.” There is no shift in attitude over time, despite that over the years, much more would have been studied on the matter and medical practice would have changed. Green’s set views were taught, leading to Registrars and other staff being under the impression that screening for cancer precursors was a waste of time. Apparently he kept an Ogden Nash quotation on his blackboard for many years saying “My mind is made up – don’t confuse me with the facts”. None of this shows any willingness to debate the evidence; on the contrary when faced with evidence of patients with invasive cancer that he had originally diagnosed with CIS though not a trained pathologist, he reclassified them and excluded them from the study. They did not fit, so he changed the evidence to suit his theory. True scepticism is not about holding an idea or defending a position but about being open to the evidence and being willing to examine it and change if necessary. Hitting on the hard edges of scientific debate is a tough experience but it serves no one if the record is distorted to hold an untenable position and legitimate questioning of this is taken to be persecution instead of honestly examining whether the position is, in fact, a correct one to hold.

References

- “The Cartwright Report”: http://www.nsu.govt.nz/current-nsu-programmes/3233.asp

- “Screening for cervical cancer” 1976: BMJ 659-60

- The Walden Report: June 5, 1976: CMA Journal Vol. 114 1003-1012

- Ostor, AG 1993: Intern. J. Gyn. Path. 12, 2, 186-92

- Lowy, I July 2010 Historia, Ciencias, Saude – Manguinhos V. 17, supl. 1, 53-67

- Heslop, B 2004: NZMJ 117,1199

- Liley, A.W. 2 November 1963: BMJ Vol 2, Issue 5365 1107-1108

- McIndoe, WA; McLean, MR; Jones, RW; Mullins, PR 1984: Obstet Gynecol. 64, 4, 454.

- Bryder, L 2009: A history of the ‘Unfortunate Experiment’ at National Women’s Hospital, Auckland University Press, Auckland

- Jones, RW; McLean, MR; 1986: Obstet Gynecol. 68, 4, 499-503.

- Sandercock, J. Burls, A. 2010, NZMJ 123, 1320

- Overton, G.H. 2010, NZMJ 123, 1319

- McCredie, M. 2010, NZMJ 123, 1321