The Plausibility of Life – resolving Darwin’s dilemma, by Marc Kirschner and John Gerhart. Yale University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-300-10865-6. Reviewed by Louette McInnes.

Continue readingEvolution in the NZ school curriculum

The teaching of evolution in New Zealand schools may seem secure, but it has faced many challenges, and these appear to be on the increase. This article is based on a presentation at the Evolution 2007 Conference, Christchurch.

Many people feel the antagonism between evolution and creationism is an issue only in the United States. However, creationism is becoming more visible around the world. Even in New Zealand, creationism, and its opposition to evolution, has a relatively long history and-as in many other countries-is currently increasing in prominence.

Evolution was first discussed in a New Zealand educational institution in 1871, when Otago University professor Duncan MacGregor pushed for the teaching of evolutionary biology. This led to moves to have him removed from his Chair, though these were ultimately unsuccessful.

New Zealand’s free, secular public education system was born in 1877. By 1881 there was some concern among the Protestant and Catholic churches that schoolteachers were being taught about evolution, thus supposedly losing the religious neutrality required of a secular system. However, school curricula contained no explicit mention of this worrying subject. New Zealanders appear to have viewed themselves as fairly open-minded in this area: Numbers & Stenhouse in 2000 noted that the NZ Herald, reporting on the 1925 Scopes trial in the US, “found it ‘hard to take the anti-evolution movement seriously'”.

However, in 1928 the Education Department published an addition to the national science syllabus that said “in the higher classes the pupils should gain some definite idea of the principle of evolution”. Though fundamentalist Christians were few in number they were extremely vocal: their immediate and heated response to the amended syllabus was so strong that the department backed down: students should not have to learn about human origins, but to “discover some part… of the great plan of nature”. This could be regarded as a win for the creationist camp, and was followed by the establishment of anti-evolution societies such as the Evolution Protest Movement.

In 1947 the Department of Education broadcasts to schools included a series of BBC programmes on evolution, How Things Began. Protest was swift and vociferous and included Labour party supporters worried about losing the wavering voter, as well as conservative Christian groups. The Minister of Education first suspended and then cancelled the broadcasts, despite strong opposition to this from teacher unions and other educationalists. Flushed with success, the creationist lobby attempted to get the Ministry to publish creationist articles in the School Journal, but the Minister declined. As public interest waned so too did the creationist movement, so that by the 1970s it seemed to have disappeared completely.

But at the same time, creationism in the US was experiencing resurgence, with the popular writings and presentations of Youth Earth Creationists such as Henry Morris (The Genesis Flood). In 1972 New Zealander Tony Hanne read Morris’ book and invited him on a tour of New Zealand. Visits by other US creationists followed, each generating considerable public interest in this country even though scientists in general rejected their claims. However, Numbers & Stenhouse (2000) also give the example of one university geologist who was so swayed by creationist rhetoric that he included works by Morris & Duane Gish in his own courses!

In 1982 the then Auckland Department of Education issued a creationist textbook for use in senior biology classes, a book which was widely distributed by the then Auckland College of Education’s Science Resource Centre. When questioned about the propriety of science teachers including creationism in their classes, a spokesman for the New Zealand Education Department responded that he found nothing wrong with science teachers including ‘scientific creationism’ in their classes, “as long as they’re presenting it as one possible explanation and not the only explanation”.

Scientists tended to feel that science, and evolution, had little to fear from creationism; it was viewed as a peculiarly American foible. Yet at the same time, the Creation Science Foundation (CSF) in Australia was expanding to become what was, by the 1990s, the world’s second-largest creation science organisation. This found fertile ground among religious conservatives in New Zealand, and also among our Maori and Pasifika communities (eg Peddie, 1995), and in 1994 the CSF opened a New Zealand branch, Creation Science (NZ).

1993 saw the introduction of a new Science curriculum, and the associated ‘specialist’ science curricula, for New Zealand schools. Evolution is mentioned explicitly only at Level 8 (Living World) of this document, which gives as a learning objective “students can investigate and describe the diversity of scientific thought on the origins of humans”. It goes on to say that students could be learning through “holding a debate about evolution and critically evaluating the theories relating to this biological issue” (my italics). This suggestion that there is more than one possible theory explaining evolution has left the door open for teachers and institutions who wish to bring creationism into the science classroom. Thus, in 1995 Peddie could comment, “… in this country some private schools, and some teachers within the state school system and home schooling systems, continue to teach creationism and debunk evolution.”

For example, in 2003 the Masters Institute, together with the organisation Focus on the Family, offered a workshop on intelligent design for teachers and parents, featuring speakers such as the Discovery Institute’s William Dembski. The session was billed as “an excellent learning opportunity that offers both a professional development opportunity and a fresh look at some knotty problems in science and biology” (Education Gazette, 22 August 2003). Focus on the Family has also distributed CD-ROMs based on the creationist tract Icons of Evolution to every secondary school in the country.

Concern from universities and the Royal Society was met by a response from the Ministry of Education stating that “it is not the intention of the science curriculum that the theory of evolution should be taught as the only way of explaining the complexity and diversity of life on Earth”-and that schools are free to decide their own approach to theories of the origins of life, within existing curriculum guidelines. Showing a lack of knowledge of evolution, the Ministry’s representative continued: “The science curriculum does not require evolution to be taught as an uncontested fact at any level. The theory of evolution cannot be replicated in a laboratory and there are some phenomena that aren’t well explained by it.”

We are now developing a new draft Science curriculum. This document, as well as emphasising the importance of students developing an understanding of the nature of science, recognises evolution as one of the organising themes of modern biology following Dobzhansky’s 1973 dictum, “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.” The curriculum document reads: “Students develop an understanding of the diversity of life and life processes. They learn about where and how life has evolved, about evolution as the link between life processes and ecology, and about the impact of humans on all forms of life”. One significant difference from the existing curriculum is that the term evolution is introduced in primary school: students in years 1 and 2 will “recognise that there are lots of different living things in the world and that they can be grouped in different ways,” and “explain how we know that some living things from the past are now extinct.” By year 13 they will be exploring “the evolutionary processes that have resulted in the diversity of life on Earth.”

The document was sent out for public consultation and the Biology component immediately drew the ire of conservative religious groups. Creation Ministries International (formerly the CSF) contacted members and supporters, asking them to lobby strongly for a reversion to the current status quo: “CMI does not suggest evolutionists be forced to teach about creation. What we do suggest is that freedom be retained for the presenting of both evolution-based and Creation-based frameworks of science. We support the teaching of evolution provided it is done accurately, ‘warts and all’, ie with open discussion of its many scientific problems included.”

And a submission for a private school stated that “… there is still no evidence to support the theory, [and]… to base [curriculum content] on an unproven theory is bizarre” (www.tki.org.nz/r/nzcurriculum/long_submissions_e.php). The writers went on to suggest that the curriculum would be better to speak of ‘diversity’, which they viewed as a much more suitable term.

There is also anecdotal evidence that many teachers also oppose the new curriculum in its present form-either because they feel uncomfortable or under pressure about it in the face of potential student, parent, and community opposition, or because they themselves have a creationist worldview. At a time when biology in its various forms is set to play an important role in New Zealand’s scientific and economic development, this is something that should concern us all.

Selected references (full references available from editor)

Numbers, R.L. & J. Stenhouse (2000) Antievolutionism in the Antipodes: from protesting evolution to promoting creationism in New Zealand. British Journal for the History of Science 33: 335-350. Peddie, W.S. (1995) Alienated by Evolution: the educational implications of creationist and social Darwinist reactions in New Zealand to the Darwinian theory of evolution. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of Auckland.

Bomby: The creationists’ favourite beetle

A knockout blow for evolution turns out to be nothing of the sort

AS JBS Haldane famously said, God must have an inordinate fondness for beetles, he made so many of them. Of all the tens of thousands of the horny-winged horde, the creationists have chosen, as the absolute knockout anti-natural selection example, the bombardier beetle. Only the great Organic Chemist in the sky could have designed the chemical weapon system which enables this beetle to deal with ants and other predators.

The special feature is a sac containing a mixture of two chemicals, which do not react with each other spontaneously. When danger threatens the beetle is able to initiate changes in this mixture which cause it to be expelled explosively. The resulting missile is not only toxic and corrosive, but also, because of the heat generated by the reaction, it is boiling hot. Some species adopt a blunderbuss or scattergun method of discharging their weapon, others are even cleverer and can aim at their target like a marksman.

To understand why creationists have been so excited, and to follow the suggested evolutionary pathway leading to this phenomenon, we must look more closely at the chemistry of the process. The storage sac contains two substances, hydrogen peroxide and a relatively simple organic compound, quinol. The latter is oxidisable to quinone, but, although hydrogen peroxide is an oxidising agent, the two can coexist without reacting if left undisturbed. When danger threatens, the sac containing this mixture is emptied into a reaction chamber containing the enzymes catalase and peroxidase. The catalase decomposes the hydrogen peroxide almost instantaneously into water and oxygen, and the peroxidase causes it to react with the quinol, oxidising it to quinone. This in turn causes two things to happen; the heat released in this reaction raises the temperature to boiling point, and the sudden release of gaseous oxygen forces the liquid out with great force. In passing, we note that the creationists have the chemistry and sequence of the process wrong, but, as is their wont, they persevere in their error after being corrected.

Why have the creationists seized on this as a clincher for their belief? Well, it’s all so complicated, isn’t it? Quantities of two unusual chemicals, two enzymes, as well as the anatomical arrangements. Each is necessary, the system would not work if any one was missing. In modern creationist jargon, it is irreducibly complex. Therefore dear old Bomby must have been intelligently designed, mustn’t he? No. It ain’t necessarily so! A plausible sequence leading from a generalised arthropod to this specialised animal can be suggested. It nicely illustrates the way features with one function can be co-opted for other purposes, and demonstrates how small steps, each conferring a minute selective advantage, can lead eventually to large changes. We can note first that each of the four chemicals is not unusual, as claimed by creationists, but is a common constituent of arthropod metabolic systems. Quinone is made by numerous insects; it ‘tans’ the cuticle making the exoskeleton more or less rigid and dark in colour. Quinol may be synthesised by a similar route; it is not confined to bombardier beetles. Hydrogen peroxide is widespread in nature as a product of oxygen metabolism. Catalase and peroxidase are also found universally in the animal kingdom; oxygen, on which our life depends, is not an unmixed blessing, and these enzymes destroy dangerous by-products of oxygen metabolism (think anti-oxidants). Greater gene activity, leading to the biosynthesis of increasing amounts of these chemicals, seems an obvious pathway of natural selection. M Isaak (2003) has linked this process to the anatomical changes which would have taken place concurrently with the chemical developments. Each step in this scheme confers an obvious advantage and so would be selected for. Though the combination of features makes the bombardier beetle unique, individually they have counterparts in many other insects; for example, the secretory glands which produce the pheromones and other chemical signals. Isaak’s article discusses the issue in more detail, and is recommended (Isaak, M. Bombardier beetles and the Argument of Design www.talkorigins.org/faqs/bombadier).

This article was suggested by my reading The Bombardier Beetle’s Chemical Defence, by Marten J ten Hoor, Hoogezand, Netherlands, in CHEMNZ, no. 100. I am grateful to Mr ten Hoor and the editors of that journal for providing that stimulus.

Opening Pandora’s Box

Demands for equal time cut both ways.

Armies of the night, science-writer and novelist Isaac Asimov once called them. He was referring to the countless millions of evangelicals who believe the book of Genesis to be literally true and therefore reject any evidence to the contrary.

President Bush is one of them. So is Michael Drake, principal of Auckland’s Carey College.

As reported in the Weekend Herald (27 August), Drake believes that one can provide dates for the main events in the history of the universe by adding up all the ‘begats’ in the Bible. The date of creation turns out to be just over 4000 BC, and that of Noah’s Flood about 2400 BC.

What can these young-earth creationists say when confronted by scientific evidence that the universe began more than 12 billion years ago, that life began over 4 billion years ago, that dinosaurs became extinct some 63 million years ago, or that fossils of our hominid ancestors are shown by potassiumargon dating to be more than three million years old?

Their best ploy is to say that God created the universe with all this contrary evidence built into it. This, says Drake, is “perfectly possible”. It seems not to bother him that this hypothesis makes God, not just a Great Designer, but a Great Deceiver as well.

And what about the ancient civilisations whose historical and archaeological records spitefully ignore the Flood and the death of all living creatures, other than the inhabitants of the ark? Clearly, God must have even more tricks up his sleeve. After all, as Drake points out, tautologically, “God is God.”

Most mainstream Christians outside the US would reject this version of intelligent design. Like fifth century St Augustine, they would say that biblical literalists deserve to be “laughed to scorn” for their “utterly foolish and obviously untrue statements.”

Adopting Augustine’s figurative interpretation of Genesis, liberal Christians believe they can accommodate the findings of science and history. Thus those who call themselves theistic evolutionists can, without contradiction, accept Darwin’s laws of natural selection as one of the laws of nature — along with those of physics and chemistry — with which God endowed his creation at the outset. No need for him to intervene on this account.

Enter a third version, one that reintroduces elements of evangelical creationism into the evolutionary story. Michael Behe, in his 1996 book Darwin’s Black Box, claimed that although evolutionary mechanisms can explain a lot, they can’t explain the emergence of certain highly complex biological systems. His examples include the flagellum of E. coli, and the human immune system.

These systems, Behe argues, are “irreducibly complex” in the sense that none of their simpler parts would have survival value until they were assembled in the right way by the intervention of a supernatural deity. Unlike theistic evolutionists, Behe believes God has to tinker with his initial design.

How scientific is all this? Well, Behe himself is a scientist. And scientists certainly do find complexity in the biological world, especially at the molecular level.

But is there scientific evidence that this complexity is irreducible? Scientists can literally see complexity. But they can’t see irreducibility. Behe has to argue for it. And his arguments have been found wanting by both philosophers and scientists.

Philosophers disparage his argument’s form: “We don’t yet understand how these complex forms could have emerged, so God must have created them”. It is a rehash of the ‘God of the Gaps’ fallacy. Flawed faith-based reasoning. Not sound evidence-based science.

Meanwhile scientists continue to plug those gaps with accounts of the evolutionary pathways that generated these supposedly irreducible systems. What becomes of Behe’s argument for an intelligent designer if all the gaps get filled?

Now to the important question: Should intelligent design be taught in schools? If so, which version?

Mary Chamberlain, curriculum manager for the Ministry of Education, says science classes should allow for some version or other. She seems to echo Bush’s recent call for ‘equal time’ for those who oppose evolution.

Equal time counts both ways. If equal time is to be given to those who think there are arguments against evolution, then it should also be given to those who think there are arguments against intelligent design. But then we get into what philosophers call “the problem of natural evil.”

If you think an intelligent designer designed the universe, then think about the unsavoury aspects of his design. Think of diseases like Alzheimers, cancer, smallpox, and those caused by Behe’s favourite, E. coli. Think of disasters like tsunamis, hurricanes, and earthquakes. If complex design demonstrates intelligence, then by the same token the “god-awful” nature of much of God’s design demonstrates defective or malevolent intelligence.

On reflection, do its promoters really want intelligent design analysed and evaluated in schools? And if so, by whom? Do they really want to open Pandora’s box?

Newsfront

In a decision which sets an important precedent for US science education, a court has ruled against the teaching of the theory of Intelligent Design alongside Darwinian evolution (BBC, 20 December). The ruling comes after a group of parents in the Pennsylvania town of Dover had taken the school board to court for demanding biology classes not teach evolution as fact.

Continue readingCommunicating the nature of science: Evolution as an exemplar

< >

>

Science as taught at school is often portrayed as a collection of facts, rather than as a process. Taking a historical approach to the teaching of evolution is a useful way to illustrate the way science works.

The need for a scientifically literate population is probably greater now than ever before, given the rapid pace of change in science and technology. Members of such a population have the tools to examine the world around them, and the ability to critically assess claims made in the media. However, there are difficulties with conveying just what science is about and how it is done; in letting people know how the scientific world-view differs from “other ways of knowing”. This is particularly evident when dealing with evolutionary theory, often described as “just a theory”, and probably the only scientific theory to be rejected on the grounds of personal belief. How can we alter such misconceptions and extend scientific understanding?

Part of my role at Waikato University involves liaising with local and regional high school teachers of biology and science. Over the past few years I have received numerous requests from local secondary school teachers to provide a resource they could use in teaching evolution. Discussion with teacher focus groups revealed a number of content areas they would like to have available:

- links to the New Zealand curriculum and to relevant web-sites,

- evolutionary process (including the sources of genetic variation and how natural selection operates),

- human evolution,

- New Zealand examples,

- evidence for evolution,

- ways of dealing with opposition among students (and colleagues),

- and the historical perspective.

These last two items are particularly significant, since modelling a way of presenting the historical development of evolutionary thought, and by extension the nature of science itself, offers a way of countering opposition to the theory of evolution.

I have deliberately used the example of evolution, because there is good evidence (eg Abd-El-Khalick and Lederman 2000; Passmore and Stewart 2000; Passmore and Stewart 2002) that altering the way in which evolution is traditionally taught offers the opportunity to show people the nature of science – what it is and how it works. For example, rather than taking a confrontational approach to their students’ beliefs, Passmore and Stewart (2000) provided a number of models of evolution and encouraged the students to determine which model best explained a particular phenomenon.

Similarly, William Cobern (1994) has commented:

“Teaching evolution at the sec-ondary level is very much like Darwin presenting the Origin of Species to a public who historically held a very different view of origins. To meet this challenge, teachers [should] preface the conceptual study of evolution with a classroom dialogue… informed with material on the cultural history of Darwinism.”

He goes on (Cobern 1995):

“I do not believe that evolution can be taught effectively by ignoring significant metaphysical (ie essentially religious) questions. One addresses these issues not by teaching a doctrine, but by looking back historically to the cultural and intellectual milieu of Darwin’s day and the great questions over which people struggled.”

Taking such an approach is highly significant in developing an understanding of the nature of science, since an historical narrative will not only place Darwin’s work into its historical and social context, but will also show how he applied the scientific method to solving his “problem” of evolution. This approach is central to the Evolution for Teaching website (sci.waikato.ac.nz/evolution – see NZ Skeptic 71; the other members of the website team are Dr Penelope Cooke of Earth Sciences, Dr Kathrin Cass, and Kerry Earl from the Centre for Science & Technology Education Research), and is also one I use in my own teaching, where every year I encounter students who have a creationist worldview. Such views may well become more common, given that there appears to be a coordinated effort to make material promoting Intelligent Design Theory (and denigrating evolutionary thought) available in schools.

This teacher-generated list, and the philosophy described above, informed the planning and design of the Evolution for Teaching website, which is hosted by the School of Science and Technology at Waikato University. First we felt it important to make explicit the nature of scientific hypotheses, theories, and laws, to overcome difficulties originating in differing understandings of the word “theory”. (Much of the language of science offers opportunities for such misunderstandings, since it invests many everyday terms with other, very specific meanings eg Cassels and Johnstone 1985; Letsoalo 1996.)

The site offers links to the NCEA matrices for Science and Biology, plus FAQs, book and site reviews, and a glossary.

Feedback has been almost entirely positive, with all the teachers attending its launch in March indicating that they would use it in their teaching and recommend it to their students. Without exception they found it attractive, easy to navigate, and informative, providing information at a level suitable for both themselves and their students. Student comments support this last point. Since the site went “live” in March 2004 it has received around 100,000 hits per month, indicative of a very high level of interest.

Evolution Website a Hit with Teachers

A Waikato University website on evolution has received overwhelmingly positive feedback from teachers, says biological sciences lecturer Alison Campbell.

“We held a teacher meeting in April for the Waikato and Bay of Plenty area from which we got some very favourable comments, but I’ve heard that teachers from Auckland and Wellington are quite taken with the site as well.”

The site is aimed primarily at providing expert support and quality material for New Zealand’s science teachers. It has been developed over eight months by a group of staff from the School of Science and Technology.

“Why did we do it? Penny Cooke and I have been concerned for quite a while now about the low level of understanding of evolutionary theory that we find in our first-year earth science and biology students. In addition, I’d been fielding requests from biology teachers for some sort of resource that could help them teach evolution.”

The team, which also includes Kathrin Cass and Kerry Earl, tried to produce a comprehensive site that dealt with many aspects of evolutionary theory and research and the related earth sciences concepts.

“We put a lot of effort into making it attractive and easy to use, and from teachers’ comments I feel we’ve succeeded in this.”

She has had other feedback, including a query from one person asking why there was nothing on “alternative theories” such as Intelligent Design. “I directed him to the site page addressing the nature of scientific theories. And then there was one from someone who intends to use the site to demonstrate the failings of scientists to their children, to counteract the teaching on evolution they’ll receive from school…”

Much of the content fits in with the curriculum objectives of the NCEA. “It was very important to us that the site has New Zealand flavour, as students are expected to be familiar with New Zealand examples of evolution.”

She feels there’s a lot of very good evolutionary material on the web, but it lacks this New Zealand focus.

The content will be reviewed annually so that the site remains accurate and relevant. “In human evolution, for example, there’s a lot of new information coming on stream every year, and it’s very hard for individual teachers to keep up with this, but we can offer them this service.”

The team felt that the sections on the nature of science and the context in which evolutionary thinking developed are essential areas of the site. “One of the main objections for many people is that evolution is ‘just a theory’. Similarly, science education research has demonstrated that students are more likely to come to accept the theory of evolution if they are given the opportunity to see how it developed, rather than just having the fact of it dumped on them.

Dr Campbell has heard that colleagues at other universities intend to use the Waikato website with their second and third-year students, and she has used it extensively with her own first and second-year classes.

“From what I’ve heard, my own students have found it a very useful resource.”

As well as dealing with the science of evolution, the site tackles, in rather oblique fashion, the old skeptics’ bugbear of creationism. Evolution is, the site says, probably the only theory to be rejected on grounds of personal belief.

There’s a section on the distinction between hypotheses, theories and laws, reinforced in the Frequently Asked Questions section, where “Isn’t evolution ‘only a theory’?” gets a clear response. The FAQs also include creationist-related queries such as: “If humans descended from monkeys, why are there still monkeys?” and, “Living things have fantastically intricate features, shouldn’t they be the products of intelligent design, not evolution?” As well as providing brief answers to these, the site has links to external sites which cover these issues in more detail.

A section titled Darwin and Religion has quotes from such people as Pope John Paul II and Stephen Jay Gould on the proper relationship between science and religion, followed by interviews with two scientists who see no real conflict between the two.

The Evolution for Teaching website is on: sci.waikato.ac.nz/evolution/index.shtml

4.6 Billion Years Worth of String

Bill Taylor explains some of the thinking behind the Time-Line installation, “Genesis Aotearoa”, at Victoria University (See also Page 13)

As a lay person I entered the world of Earth Science with a sketchy understanding and appreciation of what it entailed. Coming from an arts background there was a substantial degree of culture shock. Once this had been worked through I began to experience a rich interchange of knowledge and understanding; the interface of science and art is an exciting dynamic.

The Royal Society was concerned that while I was on Fellowship I actually learnt something. Over the years I had developed some curiosity about evolution but hadn’t pursued this beyond the school’s library. Issues such as the Big Bang, 4.6 billion years of Earth history, Chaos Theory and the expanding universe were really out of my zone of appreciation. Continental Drift theory I could appreciate but my knowledge was scant.

This curiosity blended informally and naturally with an appreciation of creation myths, such as the Maori creation myth that I often used to motivate art classes. Parallel to this was a strong sense of scepticism towards Creation Science: I always felt Genesis was yet another myth.

The prime reason for creating something like the Time Line, though, was to prove the point that art and science complement each other and enrich learning at even sophisticated levels of inquiry.

In other words, the connection goes deeper than cosmetic decoration or superficial patronage. This is a mutually worthwhile and purposeful connection, one that is not so obvious with other generic arts.

Bishop Ussher and Other Fathers of Science

In the mid-sixties, while sitting fidgeting in church, my elder brother pointed to the top of the first page of his Bible and told me knowledgeably that people thought that the world began 6000 years ago. He was referring to the Ussherian date of 4004 BC. News like this fed an already phobic imagination with visions of divine catastrophes.

Later the National Geographic and its articles on Richard Leakey’s discoveries (in the late sixties and early seventies), dated in millions of years, led me to relax a bit and see the world and my place in it as a little more tenable.

The Ussherian date provides a good lead-in to the culture of science. His scholarly and scientific use of the Bible was regarded as impeccable, thorough and unreproachable. James the First was so impressed with his approach that he had the dates included at the top of each page in the edition of the Bible that bears his name.

Ussher’s work was preceded by that of Dr John Lightfoot, Vice Chancellor of Cambridge University, who in 1644 gave an even more precise time of 9.00 am on 23 October 4004 BC.

Sir Isaac Newton played the same game. By his calculations the world began in 3996 BC. This conclusion caused alarm amongst his colleagues in the Royal Society. Some members’ theories that the Chinese Dynasties went back as much as 6000 years were rendered untenable.

Lightfoot, Ussher, and Newton represent through their rigour, and logical sequential inquiry into the evidence they held, the attributes of good scientists. This style of thinking would eventually undermine their original conclusions, as people sought and critiqued new evidence.

A Close-Run Thing

The Eugenics movement in New Zealand had legislative successes greater than anywhere in the world outside the USA and Nazi Germany

Eugenics was a phenomenon that lasted for less than a hundred years, although for some it still exists as a rational stand to take on the population problem, if not as a scientific theory. Of course advances in genetics have reintroduced the idea that we can by our own scientific efforts improve the human race. It was a theory that engaged not only some of the finest scientific, but also the finest philosophical and ethical minds of the day. It was a scientific theory that was brought to a halt less by scientific inquiry than by the moral revulsion produced by the excesses of Nazi Germany. Eugenics is interesting partly at least because New Zealand went further than anywhere else except for Germany and the US in the application of practical Eugenics in certain areas of legislation.

Francis Galton (1822-1911) began an investigation in the 1860s into the inheritance of genius, which was to have profound effects on the way people viewed the poor and the handicapped for almost 100 years. His ideas incorporated those of his cousin Charles Darwin and others who were worried that evolution might be reversed, and the human race become “degenerate” if those regarded as of little worth were allowed to breed unchecked, and the middle classes restricted the size of their families. Galton had some funny ideas about what might be inherited genetically from one’s forebears. Love of the sea for instance, as he noticed that the sons of ships’ captains often followed their fathers to sea. Galton was joined in his research and beliefs by several famous researchers including Karl Pearson, regarded by some as the founder of modern statistics.

Eugenics remained a concern mainly of a few biologists and statisticians until the first decade of the 20th century when it became very popular with certain sections of the public in particularly Europe and the US, although it did spread almost throughout the world. In Britain the popular movement was begun by Sybil Gotto, a recent widow. Many wellknown people either joined or supported the society. Cyril Burt, Havelock Ellis, Julian Huxley, John Maynard Keynes, George Bernard Shaw, all supported eugenics. Winston Churchill represented Britain at the second international congress in 1912. His views on the subject were considered so embarrassing to the government that they were suppressed until 1991. The reasons for the popularity of eugenics are complex but can probably be ascribed to perceived social problems affecting the latter half of the 19th century and the relatively new belief in science as the answer to the world’s problems. Both the popular and scientific beliefs in eugenics were remarkably resistant to the discovery of evidence refuting them.

Two family case studies came to encapsulate popular eugenics ideas about the results of degeneration. Both of these came from the US. The Jukes were a related group of misfits and criminals traceable to a single couple in New York State. The Kallikaks were a pseudonymous feeble-minded family discovered by H. H. Goddard, a prominent American eugenist who published his research about the heritability of feeble-mindedness in 1912. Eugenists continued to use these case studies as evidence of the truth of their beliefs long after they had been discredited.

Eugenists were often associated with social darwinists, who saw the solution to the problem of racial degeneration in allowing a high death rate among the lower classes to keep their numbers down. However Eugenists were interested in using social instead of natural selection to increase the proportion of the best “stock” in the racial group. The definition of good and bad stock was entirely predictable. Eugenic worth was seen as incarnate in oneself and one’s associates, and there was general agreement that many of the traits of the lower classes, such as poverty, disease, mental defect, and unemployment were not only unwanted but inherited. Eugenists generally divided people into three broad groups: “desirables”, “passables”, and “undesirables”. The desirables were almost invariably members of the Eugenists own social grouping, that is members of the academic and professional classes. The passables did change slightly over time but tended to be seen as the upper end of the working class. The undesirables could be people with mental or physical disabilities, the poor, or members of a race lower on the Victorian hierarchy of ethnic groups, the highest of which of course was Anglo-Saxon.

Popular Movement

Eugenics then, became a small popular movement among sections of the middle class responding to what they saw as the major population problems of the 20th century, sparked off by specific events, such as the poor state of health of many of the population shown by medical examinations of troops in the Boer War, and the IQ tests given to American soldiers in World War I.1 The idea was to promote eugenics as a solution to these problems by either encouraging the worthy to breed (positive eugenics) or somehow discouraging or preventing those of lesser worth from having children (negative eugenics).

The German Society for Race Hygiene was established in 1905, the English Eugenics Education Society in 1907, the American Eugenics Record Office in 1910, and the French Eugenics Society in 1912. Eugenics societies were also established in Latin America. The New Zealand society was established in 1910. In Britain and the US laboratories were funded to undertake eugenic research. Karl Pearson became the first director of the Galton laboratory for National Eugenics at University College in London, and Charles Davenport founded the Eugenic Record Office at Cold Spring Harbor in the US, which due to its generous funding could employ hundreds of researchers, most of whom were women.2

Legislation

Eugenists agitated for legislation which reflected their beliefs. This could be relatively benign. In France for instance, because Eugenists there remained Lamarckian in their outlook, they agitated for better working and living conditions for the lower classes in the belief that these conditions would produce healthier people who would pass on their good health to their descendants. In Germany however, because of their obsession with so-called racial hygiene, these beliefs eventually led to the Nazi programme of racial extermination.

Eugenic beliefs changed over time, tending to become more benign. Gradually, very gradually, scientists began to realise that eugenic beliefs simply didn’t stack up. However what was more influential was the association with the excesses of the Nazi regime, particularly in the US. Basically eugenics fizzled out from the 1930s onwards, and was regarded with loathing from 1945. Many Eugenists moved into the area of genetic counselling, advising rather than compelling the changes they wished to see. However as late as the 1950s at least one ex-eugenic researcher was employed by the tobacco industry to produce “research” showing that genetic predisposition, rather than smoking, was responsible for lung cancer.

The New Zealand Experience

Interestingly I could find no evidence of eugenic ideas in any of the New Zealand scientific journals in the 19th century. Eugenics in New Zealand was more a popular phenomenon that a scientific one. Those scientists that were interested in eugenics tended to be working in the public service rather than engaging in research.

New Zealanders did embrace eugenics enthusiastically however, when the first society was formed in Dunedin in 1910. As with the overseas experience members of these societies tended to be middle-class people, often medical or academic. Many politicians also accepted eugenics if they did not join the societies. One of the major eugenic publications, The Fertility of the Unfit was published by W B Chapple (later a Liberal MP in Britain) while he was resident in New Zealand.

The New Zealand societies agitated for eugenics to be applied to legislation in this country and began an education programme for schools and other interested bodies. As far as I could see eugenics was not as such taught in high schools or universities in this country, but some was certainly taught in training colleges, interestingly enough. (It was taught extensively in US high schools and colleges.)

Eugenists allegedly influenced the passing of the Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Act Amendment Bill of 1907, which granted divorces to those married to the insane, insanity being fairly broadly defined by Eugenists and regarded as something that could be bred out of the race.

In spite of the fact that the New Zealand eugenics societies lapsed at the beginning of World War I the fertility of the unfit remained a common cause of many influential New Zealanders. This culminated in the introduction of two bills which were to some extent designed to curb it. Part of the reason for doing this of course was economic, as the unfit were considered to be a huge drain on the finances of the state. Eugenics may have given these bills a certain scientific legitimacy which they may not otherwise have had.

The first of these was the Mental Defectives Bill of 1911. This was a large bill which set out to reorganise care of the “feeble-minded”. Much of it was concerned with classification, and treatment, and much of it was uncontroversial and of benefit to people in institutions. However a substantial proportion of the bill was concerned with the segregation of the allegedly feeble-minded from people of the opposite sex and protecting them from their own “uninhibited and promiscuous sexual nature”. People of unsound mind, and I might add that epileptics were considered to be in this category, were thought to breed like rabbits. Therefore carnal knowledge of mentally defective females became an offence, with consent of the female not considered to be a valid defence, although ignorance of her mental defect was. This bill passed with very little opposition, although MPs generally eschewed any drastic solutions to the problem such as sterilisation or contraception. Sterilisation was regarded at this time as both politically dangerous and a problem for doctors who may have been sued.

The next bill, the Mental Defectives Amendment Bill of 1928, was much more problematic, as it did include provisions for sterilisation of the unfit. Indeed a government committee of inquiry, which was set up to investigate the whole question of mental defect and sexual offending, discussed the lethal chamber with some enthusiasm. On the other hand, there was an organised and stout resistance to the bill from various politicians and members of the academic community.

Nationwide Questionnaire

The commission was a particularly thorough and large-scale exercise. A questionnaire was sent to every GP in the country, asking about numbers of mental defectives and suggestions for treatment. There was some discussion of eugenics in general in the New Zealand Medical Journal, but little about the actual bill. Very few GPs replied, and those that did tended to be scathing.

Almost everyone with any bureaucratic authority seems to have been solicited for an opinion, including the Government balneologist.3 The commission’s report was sought by a great number of organisations, from women’s groups and the major churches to the Theosophical Society. The list of organisations to which the report was sent runs to five pages and the print run for the report was very large. Overseas governments and organisations as far apart as Australia, the US and Germany also showed interest in the report.4 There seems to have been a general enthusiasm for sterilisation in the US, Germany and Scandinavia at this time. The first eugenic sterilisation laws in Europe were introduced in 1928 by the Swiss and in 1929 by the Government of Denmark. The Americans were also sterilising quite large numbers of people they judged to be mentally unfit, and had been, both informally and formally, for some years. All of this would have been apparent to the Inspector General of Mental Hospitals, when he was sent overseas to gather information for the bill.

Controversy

The bill itself had a number of uncontroversial clauses relating to the classification and treatment of so-called mental defectives. Like the preceding act of 1911 much of the bill was procedural. However certain clauses relating to sterilisation of mental defectives, the prohibition of their marriage, the new classification of “social defectives”, and the classification of children who were two years behind in their school work as mentally defective, caused much controversy. The clause relating to the sterilisation of mental defectives attracted more opposition than anything else in the bill. (Although the trade unions were naturally opposed to the social defective classification, which they thought might be used against them.)

All this resulted in a remarkably lively debate in Parliament. Although the eugenic societies had been defunct for about 10 years it is obvious that eugenics ideas were very much alive. The opposition debate in particular was both vigorous and informed. Peter Fraser, who was the best informed of the (Labour) opposition members, had obviously done some research into genetics as he quoted some of the best geneticists of the day in support of his argument for dropping the controversial clauses. He also sensibly quoted a number of examples of famous fathers who had had less than perfect sons while refuting the inevitable references to the Jukes and Kallikaks.5 On the government side the arguments tended to be less scientific, although the Minister of Health claimed to have “…searched the world’s best literature on the subject…”. On the whole though, the government arguments tended to be fairly agricultural. The member for Riccarton, for instance, likened human beings to Clydesdales.

The best debate however took place in the daily newspapers. This paralleled the various debates on this topic overseas, with those people involved with the care and control of mental defectives generally being for sterilisation, and academic psychologists being against. This debate mostly took place in the Auckland papers but did spill over into others. It seems to have been between R A Fitt, professor of Education at Auckland University College, with W Anderson, Professor of Philosophy at the same institution on the one hand, and W H Triggs, chairman of the Committee of Inquiry into Mental Defectives and Sexual Offenders on the other. The general public did not on the whole take part in this debate.

Trenchant Criticisms

Professor Fitt offered some trenchant criticisms of the science that the bill was based on. His main objection was that there was not as yet enough scientific knowledge about the measurement of mental defect, or enough work on interpreting its causes. He also believed that the psychiatrists who were to be put in charge of the classification of mental defectives were not properly competent to do so. He quite rightly stated that scientific testing should be used instead of the intuition of the psychiatrists in charge of the classification board. Triggs’ defence of the government’s position on the bill was eugenic in nature, stressing typical ideas about the unrestricted multiplication of the unfit and its cost to the taxpayer. This debate went on for some time, in the form of letters and articles from the main protagonists and others, including the Controller of Prisons, B L Dallard, on the government side, and a group of Auckland academics and educationalists including the headmaster of Kings College.6 Others who supported Fitt and Anderson were Professor J S Tennant, Professor of Education at Victoria University College, and Professor James Shelly, Professor of Education at Canterbury University College.

Other groups who might have been expected to oppose this of course were the Catholic Church and the unions. Both of these groups, like Fitt and Anderson, were quite prepared to accept quite a bit of eugenic theory at least as regards to the inheritance of mental defect, but the Church opposed sterilisation for various ethical reasons, including the idea that it was punishing the morally innocent. Neither of these groups put up a particularly vigorous fight, at least in public. Particularly the Church which, if one looks at the amount of space dedicated to these topics in the Tablet, seemed much more concerned with the threat of prohibition.

It is fairly clear why the clauses concerning sterilisation were dropped. Public reaction as such was minimal, but the vigorous attack put up by politicians and academics probably had its effect. However, if the clauses had been implemented New Zealand would have been the first country to implement legislation of this type (excluding American states) and this would have been the most extreme eugenic legislation short of Nazi Germany.

There is very little information about eugenics in New Zealand but these two books are both good general reading. Kevles, D J, 1985: In the Name of Eugenics; Knopf, New York. Paul, D B, 1995: Controlling Human Heredity, 1865 to the Present; Humanities Press, New Jersey.

Footnotes

1 These tests purported to show that recruits who were of Southern and Eastern European stock, and non-Europeans had lower IQs than Anglo-Saxons. They were later shown to be deeply flawed.

[back to text]

2 Eugenists attitudes towards women were contradictory, in that as “race mothers” womens’ major role of course was in breeding. Many women however were involved in eugenics research, possibly because they were cheaper, but some took doctorates which was apparently uncommon at the time.

[back to text]

3 The person in charge of public baths.

[back to text]

4 It is interesting to note that the German government introduced in 1932 legislation for voluntary sterilisation of various groups. Possibly the reaction in New Zealand to compulsory sterilisation influenced this legislation.

[back to text]

5 We find for instance, that Luther’s son was insubordinate and violent; William Penn’s son was a debauched scoundrel; … the son of Cicero was a drunkard….

[back to text]

6 These divisions reflect some of the debate that took place before the commission, except that two academic biologists who were consulted were both supporters of sterilisation or segregation. Others who gave evidence, including teachers, headmasters, probation officers, doctors, nurses, religious leaders and others were overwhelmingly of the opinion that mental deficiency is hereditary, that it can be easily identified, and that people with this problem should be segregated and/or sterilised if not desexed.

[back to text]

Family Obligations

Our acceptance of evolution brings with it moral obligations, believes geneticist Professor David Penny, who has been fighting for greater consideration to be given to the well-being of the great apes

From the path we gaze down at them. From their grassed mound they turn an occasional incurious gaze back – primate watching primate. I have seen very few chimpanzees. For them we are just part of an eternal procession of their depilated, camera-toting, child-accompanying, gawping kin. Behind the idling chimps, beyond the grassed enclosure with its climbing poles, beyond the zoo, rise the hills and houses of Wellington.

As we watch, one of the smaller chimps breaks away and speed-shuffles towards us. Alongside me, Suzette Nicholson the curator of primates, tenses, then relaxes. Along the way Gombi, an adolescent chimp, has picked up a broken plastic water container, and now he dippers himself a drink from the moat that separates him from us, fastidiously avoiding the muddy margin.

No good was what Suzette thought this sweet, obviously misunderstood creature was up to. “Gombi is 9 now, which is like the terrible teens, and he’ll throw things at the public if he can. He runs round trying to be big and staunch,” she explains.

Gombi is one of 15 chimpanzees at the Wellington Zoo, or, more broadly, one of the around 30-or-so great apes in New Zealand. Not many, and nor do we have the complete set. Of the species that make up the great apes – chimpanzees, orangutans, bonobos (once known as pigmy chimpanzees) and gorillas – we have only the first two. Yet New Zealand is often referred to as an example by those fighting for the great apes to be brought more fully within our circle of moral consideration, or even to be granted some form of rights.

The reason is the handful of lines in our 1999 Animal Welfare Act stipulating that any experiments with the great apes must be justified on the grounds of a benefit to the apes themselves and that these experiments must have the final approval of the director-general of Agriculture.

There has never been experimentation carried out with the great apes in New Zealand. The provision is intended at least as much as an example for others as it is for domestic consumption.

Few though they are, these lines were hard fought for by the New Zealand membership of the Great Ape Project, and one of the most persuasive of advocates was Professor David Penny. An activist by disposition – he protested the Springbok tours and the Vietnam war – he says we should accord the great apes greater consideration, letting our morality be driven by the evidence presented by our science. We now know how close to us they are. In fact, viewed through the dispassionate eyes of molecular geneticist and evolutionist David Penny, we are ourselves great apes. The differences between their species and ours are of degree, not kind.

Few though they are, these lines were hard fought for by the New Zealand membership of the Great Ape Project, and one of the most persuasive of advocates was Professor David Penny. An activist by disposition – he protested the Springbok tours and the Vietnam war – he says we should accord the great apes greater consideration, letting our morality be driven by the evidence presented by our science. We now know how close to us they are. In fact, viewed through the dispassionate eyes of molecular geneticist and evolutionist David Penny, we are ourselves great apes. The differences between their species and ours are of degree, not kind.

For the great apes – or more exactly the other great apes – life is generally far from great at all. Bonobos, chimpanzees, and gorillas are native to central and western Africa; orang-utans to Sumatra and Borneo. In these developing – or in some cases undeveloping – regions, conservation is often not a leading concern. Deforestation, the trade in baby orang-utans as pets, and, in Africa, the trade in bushmeat are whittling away great ape numbers. Their species have been given at best a vulnerable and at worst a highly endangered rating by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

In captivity, whether kept as pets or as circus animals, the great apes largely live their lives at the favour of their owners. Often this means a life arbitrarily cut short at the age of 7 or 8 when the tractable youngster becomes, like Gombi, an assertive, unpredictable and physically powerful adolescent. (Bebe, the matriarch of Gombi’s group at 40-plus, could live for another 20 years.)

In the US thousands of the great apes are used as laboratory animals. Animals used to roaming distances are kept in close quarters, infected with diseases such hepatitis or Aids, and subjected to medical procedures.

They are our substitute in experiments for one reason: they are so like us. Like us, some non-human primate species have naturally occurring osteoporosis and hypertension, some undergo the menopause, and they are susceptible to many of the same diseases that threaten human populations.

On the other hand, Penny believes the case for testing with the great apes is often overstated. Take Aids, for example. The epidemiological and laboratory evidence from human populations is actually very strong, and “we have learned virtually nothing of benefit to humans from infecting many chimpanzees with HIV”.

And his argument for ending experimentation with the great apes is much the same as that employed by those who want it to continue: the great apes are so like us.

Penny’s office is not much more than a glass cubicle inside a laboratory in a ’60s building on the Palmerston North campus. There’s a clutter of papers – apologised for with some perverse pride – and students are forever wandering to the door to seek guidance on papers or theses. Now is the most exciting time ever in the molecular biosciences, he says. Eternal questions are being answered.

Using DNA and protein sequences, Penny and his colleagues have looked at the origin and dispersal of modern humans, not only confirming the likelihood that humans originated in Africa, but also, with their finding that Maori share ancestry in a group of around 50 to 100 women, lending weight to the Maori oral tradition of the seven canoes that settled New Zealand.

The chimpanzee genome has been another particular interest. Penny sees the differences between human and chimpanzee as something of a test for whether microevolution – small changes over generations – is enough to account for macroevolution, the more major differences between species.

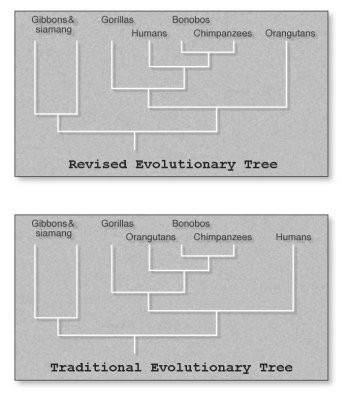

One estimate puts the genetic similarity between chimpanzees and humans at 98.76 per cent. (If you want to quibble you can find a smidgen more or less difference by selecting different categories of DNA.) Counterintuitively this makes us more closely related to chimpanzees than chimpanzees are related to gorillas.

DNA sequencing can also be used to put dates to our evolutionary history. The difference between chimpanzee and human DNA has come from the mistakes that are made as the DNA is copied from generation to generation. The errors occur at a reasonably constant rate in certain types of DNA. So if you know the rate, can compare the two DNA sequences, and have some sophisticated mathematics at your command, you can arrive at a date for a common ancestor.

The common ancestor of man and chimpanzee turns out to have walked the earth about 6.5 million years ago. Although this is around half a million years before the Grand Canyon started to form — and although it has to be realised that this is 6.5 million years in which chimpanzees and humans have evolved down their respective paths – in evolutionary terms it is the blink of an eye.

So close is our genetic makeup to that of the other great apes that the question for Penny and others like him is not why humans are so similar to the other great apes, but rather how to account for the differences. Penny’s answer: our species has a much longer growth period during which the brain and body are increasing in proportion.

If evolution seldom creates features out of nothing – and microevolution is sufficient to explain macroevolution – then we should expect our own attributes in the other great apes. And the more closely researchers look, the more this turns out to be so. Chimpanzees employ mental representations. They are self- aware. They are capable of deceit. They use tools. They transmit culture. They can acquire language.

In the mornings at Wellington Zoo the chimpanzees are given cups of blackcurrant drink fortified with vitamins. Overnight the female chimpanzees have been segregated – a welcome break from the attentions of the males. The status conscious males line up to be passed their drinks. The females and infants extend their hands through the bars in a prehensile tangle. The hands are rough and powerful; they look as if they have been crafted from black latex.

As the males head back outside to join the females they let loose with a rising anarchic chorus of pant-hoots.

Anatomy is destiny. The smartest of chimpanzees is still not going to be able to talk. They lack the breath control and physical equipment to do so. Nor should we expect a watchmaker chimpanzee. See how well you do at manipulating objects if you stop using your opposable thumb.

But if “chatting to a chimp in chimpanzee” – to quote the Doctor Dolittle song – isn’t going to happen, having a conversation is still possible. Beginning with Washoe the chimpanzee in the 1960s, numerous great apes have been taught Modified American Sign Language or have been shown how to communicate using the lexigrams on symbol keyboards.

But if “chatting to a chimp in chimpanzee” – to quote the Doctor Dolittle song – isn’t going to happen, having a conversation is still possible. Beginning with Washoe the chimpanzee in the 1960s, numerous great apes have been taught Modified American Sign Language or have been shown how to communicate using the lexigrams on symbol keyboards.

At age 5 Washoe the chimpanzee was capable of using more than 100 signs and understanding hundreds more. Panbanisha, a bonobo, can produce about 250 words on a voice synthesiser and understand about 3000. Koko, a 26-year-old gorilla is claimed to understand about 2000 words of English and to have an IQ of between 70 and 90. These acculturated apes produce an extraordinary effect on those who meet them.

“I have been strongly influenced by some of the chimps who have been taught American sign language, and once you look a chimp in the eye and see something there that is different from a dog, you have a different perspective,” says Massey primate expert Arnold Chamove, who has met the likes of Washoe, and Lucy, who was raised from infancy by American psychologists, the Temerlins.

The Temerlins, who seem to have been like-totally-60s, raised Lucy as one of their own children, to the point that she had become, as primatologist Jane Goodall put it, a changeling, neither chimpanzee nor human. Lucy was accustomed to serving tea to guests, fixing her own pre-dinner cocktails, and masturbating to Playgirl centre-spreads. Eventually the Temerlins felt it best that Lucy move on, and she was sent to Gambia for a difficult and lengthy rehabilitation back into the wild.

“She was sent away from her family to be rehabilitated and she was depressed,” says Chamove. “I had worked as a clinical psychologist, so I knew a bit about depression. It was just like someone had taken a 5-year-old out of her family and put her in a zoo with some chimpanzees. And she was thinking ‘Jesus Christ, how long is this going to last?’ No blankets, no beds, no food she was used to.”

Could it be that Chamove was over-empathising?

“I didn’t see any substantive difference [between Lucy and someone in the same situation].”

For Suzette Nicholson at the Wellington Zoo the chimpanzee colony has all the continuing interest of a long-running and perfectly comprehensible soap opera. Recently a palace coup ousted the dominant male. “Mahdi, the youngest of the big males wanted to take over, so he tried to beat up Boyd, the alpha male, when he had been sick. What happened was that the girls all ganged up on Mahdi and chased him around the park at full speed. Now the three males share power.”

When one of the babies died the colony went into mourning. “We let the mother keep the baby for a couple of days until it became a health hazard and we took it off her. When we did, all of the other females would sit round her, grooming her and fussing over her. They do grieve. One of our females died not long ago while under anaesthetic. After she died we let the other chimps in to see that she was dead and wasn’t coming back.”

As it becomes ever more evident that we are as much the product of evolution as any other creature, and that evolution has no higher goal, so Penny hopes the centuries-old paradigm of the Great Chain of Being (GCB) will begin to crumble. The GCB is the notion that there is a progression of living things: from creatures barely alive on the lower rungs, to sentient then rational beings, and, above that, beings that are no longer anchored to material existence. Less perfect beings are there to serve more perfect beings. The GCB is us-and-them. Animals and us.

Penny finds the quote he wants and recites with theatrical enjoyment: “‘There is none that is more powerful in leading feeble minds astray from the straight path of virtue than the supposition that the soul of brutes is the same nature of our own.’ Isn’t that wonderful?”

This is the 17th century French philosopher René Descartes, but the GCB’s pedigree can be traced back to the ancient Greeks. Plato, for example, thought there were three different kinds of souls: the primitive, the mortal and the immortal, but that the immortal soul – the one that counted – resided strictly in humans, and even then not all of them; children and slaves, for example, were out of luck. The ancient Greek thought meshed nicely with the part of Judao-Christian teachings that put all of nature at man’s disposal, and in the fifth century Saint Augustine folded the one into the other.

Penny sees the GCB as a licence for environmental despotism and will be pleased to see an end to it.

As for the law, this is a 3000-year old accretion of precedent which generally holds animals, no matter how intelligent, to be no more than property. And property can neither suffer injury nor sue; injury can only be done to the owner. Hominum cause omne jus constitum – the law was made for men and allows no fellowship or bonds of obligation between them and the lower animals – runs a tag derived from Roman law. In his book Rattling the Cage, Harvard law lecturer Steven Wise puts a case for legal personhood for the great apes, but it seems unlikely that this will happen any time soon. Still, it is well to remember that it is only within relatively recent times that various groups of humanity have gained fundamental civil rights.

What Penny and his fellow members of the New Zealand Great Apes Project have wanted has been more modest. Steering clear of the contentious issue of rights, they would have liked to introduce a system of legal guardianship into the An-imal Welfare Act as a pragmatic way of dealing with the courts. In the end, the backlog of legislation awaiting Parliament in the lead-up to an election dictated what was achievable.

Of course if we admit the great apes within a widened circle of moral consideration, it begs the question of where to next. If we extend rights to the great apes, then what about those other primates that exhibit similar attributes, if to a lesser degree?

Making more of a species leap, what about, say, whales? While it is easy enough to imagine oneself inhabiting the mental landscape of a primate, says Penny, the world of a whale is almost unknowable. So much of how we perceive and interact with the world is defined by our bodies and our senses. If you put two blind people in a room they will still use hand gestures to emphasise what they are saying. Such things are hard-wired. Comprehend how the world must seem to a whale – how can we?

Questions answered with questions. If we are to discuss the issues surrounding our treatment of the great apes, then Penny seems keen that we discuss the particular issues, and not go haring off to who knows where.

Yet with the Great Chain of Being displaced by DNA’s double helix it seems hard to see this debate as anything other than the harbinger of many others to come.

David Penny will be speaking at the Skeptics’ Conference in Wellington, September 19-21.

Reprinted from Massey University Alumni Association newsletter with the author’s permission.

Devil’s Chaplain an Eloquent Advocate

A DEVIL’S CHAPLAIN: Selected Essays. Richard Dawkins. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003. ISBN 0 297 82973 4.

We Dawkins fans have been waiting since “Unweaving the Rainbow” in 1998 for this. Unlike its predecessors, it is not written around a single theme, but is a collection of Dawkins’s comments and reviews of the past 25 years, on a variety of topics, reflecting his wide-ranging interests and passions. His editor, Latha Menon, has arranged 32 of these into six groups and a final letter to his ten-year-old daughter on “Belief”. In addition to a general Preface, Dawkins has written a short introduction to each group.

The first essay in group one, which gives its name to the title of the book, is based on a quotation from a letter of Darwin’s: “What a book a Devil’s Chaplain might write on the clumsy, wasteful, blundering low and horridly cruel works of nature”. This is a mixed bag of topics, ranging from the lunacies of crystal gazing and postmodernism to an enlightened public school headmaster of 100 years ago, with, between these extremes of sense, the Great Ape Project.

In the second group, collected under the title, ‘Light Will Be Thrown’, we are back with Darwin and evolution. ‘The Infected Mind’ is a passionate denunciation of monotheism, after which Dawkins cools down by means of four eulogies for friends and heroes.

Much is made, especially by biology’s enemies, of “hostility” between Dawkins and SJ Gould. A whole section of the book is devoted to this; reviews of Gould’s books, comments on his philosophy, and correspondence between them. It is a lesson in how to combine professional disagreement over details with warm respect and friendship in personal matters. The author grieves for Gould’s early death as for a fellow fighter for truth.

The final section has a geographical flavour. “Out of Africa” applies to Homo sapiens in general, and to Dawkins in particular, and he relishes that. Many of us parents must wish we could write as eloquently to our children as he does in the coda to the book. Fortunate Miss Dawkins!

Warwick Don replies

I deny any fudging on the use of the word “creationist”. I make a clear distinction between young-earth creationism and intelligent design (ID) creationism, at the same time indicating a link between the two. In my article in Investigate magazine (November 2002), I write: “there are several types of anti-evolutionary creationists”, implying that there are also pro-evolutionary creationists. So I object to being accused of bandying the term (creationist) around.

Continue reading