The world-wide panic over the MMR vaccine was sparked by the actions of one doctor who breached several standards of scientific practice. This article is based on a presentation to the 2010 NZ Skeptics conference.

Every few years, the World Health Organisation (WHO) publishes a series of ‘death tables’, a summary of how many people died in a given year and the causes of death. The tables make interesting reading. The figures published for 2004 show that a third of all deaths worldwide were due to infectious diseases, a staggering 15.1 million people1. Of these, four million may have been prevented by vaccination.

As a microbiologist, I am staggered by the growing anti-vaccination movement. Vaccination has to be the success story of ‘modern’ medicine. Just look at the benefits: vaccination can provide lifelong protection, does not rely on correct diagnosis or treatment being available and can avoid some forms of auto-immune disease that can be triggered by infection. As the saying goes, prevention is better than a cure. While it is true that vaccines are not 100 percent risk-free, the benefits to both the vaccinated individual and the wider community (through ‘herd immunity’) far outweigh the risks.

What is fascinating about vaccination ‘hysteria’ is that different countries have different scares, even though they are using the same vaccines. One such scare, which has resulted in a resurgence of measles in a number of countries, relates to the MMR vaccine. This is a freeze-dried preparation of three living but disabled viruses: measles, mumps and rubella. In the 1990s, a British doctor by the name of Andrew Wakefield claimed there was a link between MMR vaccination and autism. He claimed to have discovered a new syndrome, which he called autistic colitis, in which autistic children were found to have a particular kind of gut disease.

He also claimed to have found that the appearance of symptoms of autism coincided with MMR vaccination, and children with autistic colitis had measles virus in their guts. His findings were based on a study of 12 children with developmental and intestinal problems, published in the Lancet medical journal in 19982. Nine of the children were diagnosed with autism. The children were believed to have been developing normally and then suddenly regressed, and parents were asked to recall how close to the time of MMR vaccination the symptoms appeared.

The study suffers from a number of crucial flaws, not least the lack of blinding or control groups, or potential for parents to incorrectly recall the appearance of symptoms. It also turned out that Andrew Wakefield had numerous conflicts of interest: he was receiving money from lawyers looking to build a case against a vaccine manufacturer, had submitted a patent on an alternative measles vaccine, breached ethics compliances and even paid children at a birthday party for donating blood.

The journalist Brian Deer was instrumental in bringing all of these conflicts to the public’s attention and has maintained a website (briandeer.com/mmr-lancet.htm) summarising his investigations into Wakefield and the MMR debacle. Recently, the British Medical Journal (BMJ) commissioned Deer to write a series of articles summarising his findings3-5. In 2010, Andrew Wakefield was found guilty of misconduct and struck off the medical register in the UK and the Lancet finally retracted his paper.

In an editorial accompanying one of Deer’s articles, the BMJ’s editors asked:

“What of Wakefield’s other publications? In light of this new information their veracity must be questioned. Past experience tells us that research misconduct is rarely isolated behaviour.”

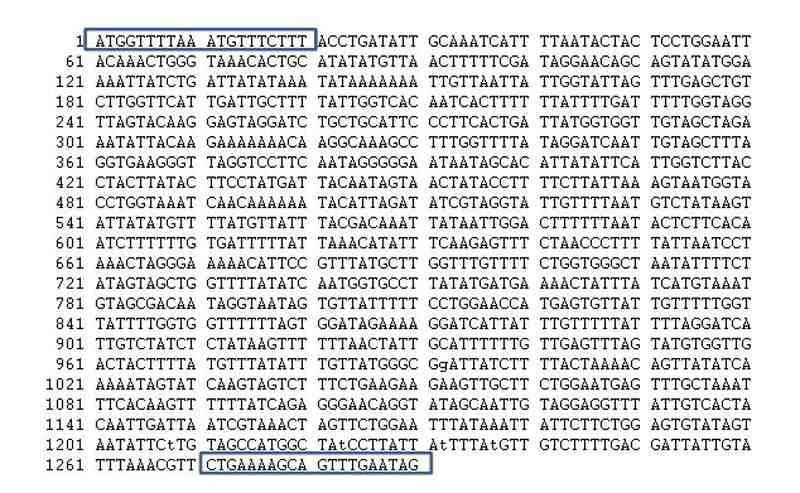

What of his other work? Indeed, the Lancet paper was just the first in a series of papers by Wakefield attempting to link autism with measles. One of the things he showed was that measles virus could be detected in the guts of autistic children using a technique called the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). PCR is a fantastic technique used to amplify very small amounts of target genetic material to generate over a billion copies. In a nutshell this means PCR can take something that is undetectable and make it detectable. However, one of the downsides of such a sensitive technique is that it is very easy to contaminate, so proper controls are really important. For those who want to know how PCR works, there are some very nice videos online (youtube/eEcy9k_KsDI).

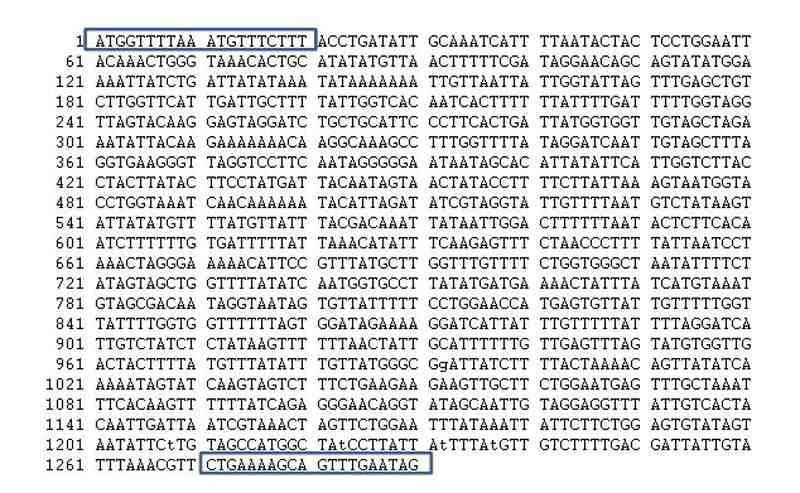

One of the crucial things needed to carry out PCR is a set of very specific ‘primers’ which recognise the region of genetic material that you want to amplify (Fig 1). You need primers to each end of the region of interest and then PCR amplifies the bit between the primers. So if the primers match the wrong region, you will end up with a large amount of the wrong thing, a classic case of garbage in, garbage out. So the important things to remember are:

- The primers need to be specific so that they only amplify what you are targeting and nothing else.

- You have to be very, very careful not to contaminate the reaction.

To make sure the primers are specific and nothing has been contaminated, it is crucial to include a number of controls alongside the samples being tested:

- A negative control which has water in place of any target genetic material which will tell you whether you have had a contamination problem or not.

- A negative control which has control genetic material that does not contain any of the target sequence which will tell you if your primers are specific enough.

- A positive control which has genetic material that does contain the target sequence which will tell you if your reaction has worked.

So, you have your samples and your controls, the PCR machine has done its dash and you are left with a little tube filled with billions of copies of the target sequence (or none if the sample was negative…). This can then be visualised by gel electrophoresis and you are left with something like the picture in Fig 2.

Lane 1 contains a size standard, lane 2 is the negative control containing no genetic material, lane 3 is the negative control containing no target sequence (the very faint band is just the background genetic material), lane 4 is the positive control containing the target sequence and lanes 5 and 6 are our unknown samples (which in this case are all positive). It is important to say here that very rarely would you see an actual gel published in a paper. Most results are just described as the number of positive or negative samples. This is important as it leaves the reader assuming the correct controls were done. But it doesn’t end with gel electrophoresis. To make absolutely certain, the amplified genetic material can be sequenced to confirm it is the correct thing. And if the claims you are making are wide-reaching and/or controversial then sequencing is exactly what should be done.

Andrew Wakefield hypothesised that exposure to the measles virus in the MMR vaccine was a factor in the emergence of his so-called ‘autistic colitis’ and that genetic material from the measles virus would be found in patients with the disease but not healthy controls. He supervised PhD student Nick Chadwick to investigate. The first paper they published (in January 1998) was in the Journal of Virological Methods, reporting a “rapid, sensitive and robust procedure” for amplifying measles RNA6. In August 1998 they published a second paper describing the use of the procedure to look for measles virus in samples from patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)7. They state:

“These results show that either measles virus RNA was not present in the samples, or was present below the sensitivity limits known to have been achieved”.

They then went on to look at the children reported in the, now retracted, Lancet paper (that is, the ones with ‘autistic colitis’). Wakefield never published these results but Nick Chadwick did write up his PhD thesis in 1998. Brian Deer has put the relevant information from the thesis on his website (briandeer.com/wakefield/nick-chadwick.htm). Nick Chadwick concludes: “None of the samples tested positive for measles, mumps or rubella RNA, although viral RNA was successfully amplified in positive control samples”. Despite this negative result from 1998, Wakefield then appears as senior author alongside a team of Japanese researchers in a paper published in April 2000 in the journal Digestive Diseases and Sciences8 where they report the detection of measles virus:

“One of eight patients with Crohn disease, one of three patients with ulcerative colitis, and three of nine children with autism, were positive. Controls were all negative. The sequences obtained from the patients with Crohn’s disease shared the characteristics with wild-strain virus. The sequences obtained from the patients with ulcerative colitis and children with autism were consistent with being vaccine strains.”

In 2002 Wakefield then published another, bigger study of children suffering ‘autistic colitis’ with a team from Ireland9. They reported:

“Seventy five of 91 patients with a histologically confirmed diagnosis of ileal lymphonodular hyperplasia and enterocolitis were positive for measles virus in their intestinal tissue compared with five of 70 control patients.”

Yasmin D’Souza and colleagues at McGill University in Canada published a very nice study in 2007 in which they compared the primers used by both the Japanese and Irish groups with their own primers for the measles virus on a range of IBD and control intestinal biopsy samples10. Any positive samples were verified by sequencing.

And the results? The primers used by Wakefield and colleagues weren’t specific for measles virus. In fact, the amplified fragments were found to be of mammalian origin. What this means is that human samples should all be positive. Unsurprisingly, when D’Souza tried using genuine measles specific primers they “failed to demonstrate the presence of MV [measles virus] nucleic acids in intestinal biopsy samples from either patients with IBD or controls”. They also failed to find any measles virus in samples taken from over 50 autistic children11. This does suggest that Andrew Wakefield’s research conduct does not stop with the Lancet study.

There is now a huge body of evidence indicating that there is no link between vaccination and autism. Despite this, Andrew Wakefield is held up by many as a hero, fighting a corrupt system with the ‘evil’ pharmaceutical industry at its centre. Wakefield has recently published a book entitled Callous Disregard: Autism and Vaccines – The Truth Behind a Tragedy. One reviewer wrote:

“Dr. Wakefield sets the record straight. It was not he who showed callous disregard towards vulnerable, sick children with autism. It was the British medical establishment, the General Medical Council, the media and the pharmaceutical industry that threw the children under the bus to protect the vaccine program. This is a book for everyone who cares about our future”.

Who needs evidence, hey?

References

- WHO website. www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/en/

- Wakefield AJ, Murch SH, Anthony A, et al. (1998). Lancet 351(9103): 637-41. RETRACTED.

- Deer B (2011). BMJ. 342:c5347. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5347.

- Deer B (2011). BMJ. 342:c5258. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5258.

- Deer B (2011). Secrets of the MMR scare. The Lancet’s two days to bury bad news. BMJ. 342:c7001. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c7001.

- Chadwick N, Bruce I, Davies M, van Gemen B, Schukkink R, Khan K, Pounder R, Wakefield AJ (1998). Virol Methods. 70(1):59-70.

- Chadwick N, Bruce IJ, Schepelmann S, Pounder RE, Wakefield AJ (1998). J Med Virol. 55(4):305-11.

- 8. Kawashima H, Mori T, Kashiwagi Y, Takekuma K, Hoshika A, Wakefield A (2000). Dig Dis Sci. 45(4):723-9.

- 9. Uhlmann V, Martin CM, Sheils O, Pilkington L, Silva I, Killalea A, Murch SB, Walker-Smith J, Thomson M, Wakefield AJ, O’Leary JJ (2002). Mol Pathol. 55(2):84-90.

- D’Souza Y, Dionne S, Seidman EG, Bitton A, Ward BJ (2007). Gut 56(6): 886-888.

- D’Souza Y, Eric Fombonne E, Ward BJ (2006). Pediatrics 118(4): 1664-1675.