Jim Ring continues his investigations into the Fijian paranormal scene.

I HAVE previously examined supernatural claims from Fiji [see NZ Skeptic 26 & 35]. Twenty odd years ago a friend described the fire-walking he had seen there (he was very impressed), but he had also heard that with sufficient faith, religious devotees could immerse their hands and arms in boiling oil. This seemed both incredible and inexplicable.

Last year in Fiji I acquired a book which sheds considerable light on the mystery. This is Holy Torture in Fiji published by The South Pacific Social Sciences Federation (1974). It is a joint effort involving five authors and a photographer. The section of most interest was written in 1970 by Muneshwar Sahadeo (who went through the ceremonies) and Sister Mary Stella, a nun, (who observed them).

An annual festival to worship the goddess Durga was celebrated in Suva. In 1969 a new priest, Ram Nath from Northern India took over and included examples of what the book calls “Holy Torture”. This involved flogging or whipping, walking or dancing on blades, tongue piercing (and piercing of other parts of the body), and taking a sort of dumpling out of boiling ghee using a bare hand. Ram Nath deliberately wanted to exclude fire-walking as it is a religious rite from Southern India and it is also associated with tourism.

This is a curious book. Its publication was undertaken by an academic who must have read the description of Ram Nath’s ceremony and then arranged for two more observers to describe a fire-walking ritual from another temple. In 1971 he observed Ram Nath’s ceremony himself and later, in 1972, he arranged for a professional photographer to attend the ceremonies. Thus the book is illustrated with some excellent photographs, many in colour, so it is possible to compare the description in the text with a picture of what may really have occurred. Finally he (Professor Ron Crocombe) attempts an explanation without resorting to the supernatural. He largely succeeds, except for the “bare hands in boiling ghee” which (if the text is to be believed) completely defies rational explanation.

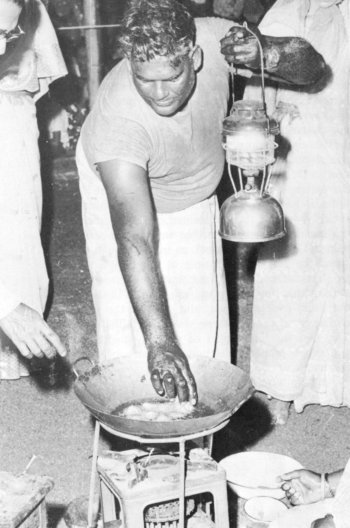

Most of the ceremony took place in daylight. But the important part (from the skeptic’s viewpoint) took place after dark in the light of a pressure lamp. According to the text, ghee (butter oil) was heated to boiling point (measured at 130oC with a thermometer) and gulagulas were cooked in it. These are described as “like doughnuts”, but “dumplings” might be a better description. When the gulagulas were cooked the priest plunged his hand into the boiling ghee and lifted several out. Then he took the hand of each participant in turn, plunging it into the boiling oil. Later each participant lifted a cooked gulagula out by himself.

One of the authors (Muneshwar Sahadeo) was a participant and he (and all the others in the ceremony) reported feeling only a pleasant warmth when his hand was in the boiling ghee. The cooked gulagulas were then handed to the audience who “found them hot and extremely difficult to hold”.

If all this were true it would seem we have a genuine miracle. But we do not have to rely on the text. Would it not be great if there was always a professional photographer to record miracles? The really amazing thing about this book is that the authors do not seem to have looked at the photographs. Indeed, they were taken after the accounts were written. But Crocombe must surely have seen them and, if so, we have clear evidence that he is capable of ignoring the evidence of his own eyes.

Crocombe’s summary does cast doubt on several points in the primary account. When he attended the ceremony in 1971 he received a gulagula from the priest and reported that it was “very hot but not unbearably so”. Furthermore, all the gulagulas examined were undercooked.

So, what can we make of this? Firstly, the ghee was not boiling; 130oC, though hot enough to injure human flesh, is too low a temperature. The gulagulas were floating and bubbling but the bubbles were water vapour, not oil. This is always the case when food (potatoes for example) is cooked in hot oil. As they were floating, they could be removed from the oil without immersing any part of the hand or fingers, while Crocombe tells us that they were not hot enough to damage human tissue. One of the photos shows a participant removing a gulagula by sliding it up the gentle slope of a wok. This is rather like the old Christmas game of snapdragon where raisins are plucked from burning brandy.

The clincher comes from two photos of Ram Nath and their caption. This states: “Ram Nath puts his right hand in the boiling ghee. …Ram Nath kept his hands totally immersed and stirring the bottom of the pan for five to seven seconds at a time.”

But the pictures show nothing of the sort. In one he is taking hold of a gulagula while carefully avoiding the ghee. While in the other he is apparently waving his hand above the surface of the oil.

So how could the audience (who are shown watching closely) be so easily fooled? Well, the only lighting is from an oil pressure lamp, which throws a good light but casts sharp shadows. In the first picture the priest holds the lamp high so all can see (when nothing miraculous is going on). But for the second, when the “miracle” is taking place, he has placed it down on the ground so that the oil surface is in shadow. However, the photographer has used a flash so we can see much more than the audience could. The priest’s hand and the oil surface are not in shadow to the flash but well illuminated, and he is performing an illusion. I presume, like all good illusionists, he told the audience what they were seeing (or rather what they were supposed to see).

I cannot explain how the priest convinced Muneshwar Sahadeo that his hand was immersed in boiling ghee, but then Muneshwar Sahadeo does not tell us what convinced him. However the photographs, taken two years later, clearly show an illusionist at work. One could argue of course that when Muneshwar Sahadeo and Sister Mary Stella watched the ceremony in 1970 the priest was working genuine miracles, whilst by 1972 with the photographer present his powers had waned and he had to resort to trickery. Such unfalsifiable hypotheses have no place in science, and skeptics demand far better evidence before they can accept such phenomena as miraculous.