Ethics and morality are often regarded as beyond the reach of scientific inquiry. But certain values appear to be shared by all humans as species-typical adaptations. This article is based on a presentation to the 2011 NZ Skeptics conference in Christchurch.

It was a pleasure to speak at the annual New Zealand Skeptics conference last year and hear from people representing a rich variety of scientific disciplines and other community organisations. A special thank-you to everyone who travelled from outside of Canterbury to support us following the recent earthquakes. I’m sure your lives are richer for visiting what is left of our city and sharing a few mild aftershocks with us! We enjoyed the morale boost from the weekend of friendly visitors, thoughtful presentations, light-hearted poetry, feasting and court theatre jesters, and the general atmosphere of proactive prosociality.

Relating to all these matters in the broadest possible sense, I discussed the subject of morality and morale. The theme of the conference was ‘building on solid science’, and I suggested that human wellbeing might be built upon a body of six core values. While my talk and this article are insufficient to address the topic fairly, I think a useful introduction can still be made, while avoiding an approach that would be either too complex or simplistic. I also mentioned the matter of priority – there may be many things that are important, but if everything is important, then nothing is important. Here I am aiming for what is most important.

I welcome questions, criticisms, assistance, and general sceptical inquiry of the points I make. Working as a clinical psychologist in a hospital injury and trauma service following the earthquakes, I cannot guarantee I will have time to respond individually to such feedback, but I will read it all and please know that I sincerely appreciate it.

What is Morality?

Morality is a subject that addresses big questions of existence. Who am I? Why am I here? What should I do? With varying degrees of awareness, everyone learns answers to such questions through processes of imitation, instruction, and inference. The answers take the form of moral models, which are ideas about human nature and right and wrong. Such models are explicit (acted upon with reflection), or implicit (acted upon without reflection), and impact the wellbeing of humanity’s billions on a daily basis.

Historically, considerable scepticism about moral models has been evident. “Those who promise us paradise on earth never roduced anything but a hell,” stated our own Professor Sir Karl Popper, summarising prior efforts of a utopian character. However, within many academic disciplines there has been an even stronger statement, a Humean consensus that science must concern itself with answering descriptive ”is’ or ‘fact’ questions, rather than prescriptive ‘ought’ or ‘value’ questions. This has been accepted as a truism by many, with attempts at scientifically based moral or value reasoning criticised as ‘scientism’ or the ‘naturalistic fallacy’, with dire predictions.

Challenges to these charges of scientism have arisen in recent years (Baschetti, 2007; Brinkmann, 2009; Kristjansson, 2010(, perhaps most influentially and eloquently from the philosopher and neuroscientist Sam Harris, in his 2010 book The Moral Landscape. In his book, Harris attacks moral relativism with a perceptive argument for scientific moral realism. As Harris explains, every single scientific ‘is’ statement ultimately rests upon implicit ‘ought’ statements – “all the way down” (p 203).

What logic can prove logic itself? What if you don’t value logic or empiricism? In such a case you destroy all of science, not just moral claims. 2+2=4, but only if you value mathematics. If people do not share such values there may sometimes be no way to convince them. However, there is also no need for the rest of us to take their arguments seriously either – any more than we need to convince everyone that physics or medicine can be helpful before we use it to improve at least our own wellbeing. Harris also argues that moral claims are universally claims about the wellbeing of conscious creatures (real or imagined), an area increasingly well illuminated by neuroscience and other sciences of the mind. In reality there is no choice but to go from ‘is’ to ‘ought’ and science offers the safest path to action, due to the collaborative scepticism and empiricism of scientific peer review process. These points and more are elaborated upon in his book, and I recommend reading it to examine the case in persuasive detail.

Ultimate, Universal, Unavoidable

The Moral Landscape argues that a science of human wellbeing is possible, based upon neuroscience and other sciences of the mind. Indeed, this is the very field of clinical psychology, broadly defined. Given evidence emerging and converging from the scientific literature, I would like to advance further and suggest that human wellbeing may be associated with six core moral values that are ultimate, universal, andunavoidable. I will briefly summarise and explain what I mean by this.

I use the word ultimate in the sense of evolutionary origins (Scott-Phillips et al, 2011) and values coded at the level of the genotype (Yamagata et al, 2006) that develop through processes of epigenesis (feedback effects of culture/environment upon genetic expression). Simply put, social organisms including humans must develop systems to (1) perceive patterns in their environment: (2) allocate time between competing needs: (3) regulate social relationships: (4) value inclusive fitness: (5) defend against threat: and (6) maximise all of these abilities within homeostatic limits. Certain system organisations tend toward Nash equilibrium or evolutionarily stable strategies, that outcompete other strategies. In other words, these values may not only be how life is, but how life must be, for reasons ultimately reducible to the laws of chemistry, physics and mathematics. Historically, evolutionary modelling using game theory simulations has been a prominent scientific tool in exploring the nature of such systems, for example in the domain of social relationships (Axelrod & Hamilton, 1981).

Six values also appear to be universally shared by humans as species-typical adaptations, as suggested by psycholexical and cross-cultural research. Psycholexical theory posits that because languages evolved, they are likely to contain words for patterns in the world (including patterns of valued personality) that are important to human wellbeing.

Across world languages, the thousands of words for describing personality appear to cluster in six main domains (Lee & Ashton, 2008). Additionally, across world ethical codes, philosophies and religions, six core values seem to be shared. They apply across the literature traditions of Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, Hinduism, Athenian philosophy, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, and also seem integral to oral traditions ranging from the Masai of the African savannah, to the Inughuit of Arctic environs (Dahlsgaard, et al, 2005). Specific expression of these varies, as do a range of non-shared values. However, the cross-cultural nature of these six core values refutes claims of moral exclusivity by any one tradition, and given the thriving of societies lacking the non-shared values, these appear less generally important and perhaps even obfuscating or detrimental in some cases (Paul, 2009).

Six values also seem unavoidable, in the sense that people must develop them to at least a minimum degree to survive, and to a higher degree to thrive. Failure leads to high levels of dependence or institutionalisation – ranging from requirements for supported living arrangements, to psychiatric hospitalisation or prison. For example, low levels of intelligence characterise intellectual disability and dementia, and low levels of altruism characterise psychopathy. Conversely, high-level development of such values aides flourishing – enhanced wellbeing via autonomy, social connection and competence. These patterns of negatively and positively developed characteristics are the focus of psychiatry and clinical or applied psychology.

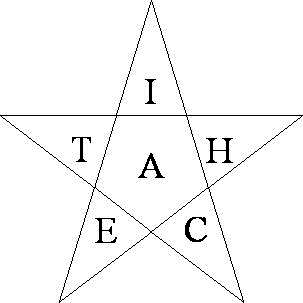

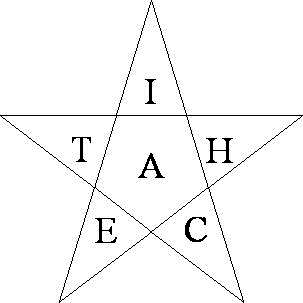

I.T.E.A.C.H.

I have used the mnemonic I.T.E.A.C.H. to summarise six values, each letter representing a value word. An important caution is that this word set is only one possibility from hundreds of potential words across the six domains (Ashton et al, 2004). It is selected for memetic reasons, including being easy to remember, descriptive and prescriptive – and with the star for associations with light and enlightenment, bright and magical things, aspiration and inspiration, and matching the embodied metaphors of our intuitive folk psychology (Blackmore, 1999; Seitz, 2005; Winne & Nesbit, 2010). You probably have your own meaning attached to these words, but that meaning is not what I mean, or at least not only. Instead they refer to diverse but related phenomena across physical, biological, psychological and sociological levels of knowledge (Henriques, 2003), with consilience or ‘unity of knowledge’ as an aim (Wilson, 1998). “Words are only tools for our use” as the biologist Richard Dawkins has said (Dawkins, 2006). Nonetheless we must choose some words to use and these seem adequate. Choose your own if you prefer.

To briefly summarise these values then, Intelligence might be parsimoniously defined as pattern recognition, with some other words that cluster in this psycholexical domain being knowledgeable, perceptive, educated, curious. Temperance refers to the ability to temporally sequence actions adaptively, with some other words in this domain being conscientious, self-disciplined, organised, systematic. Equality refers to the ability to maintain mutualistic or non-zero-sum social relationships, with some other words in this domain being just, fair, honest, humble. Altruism refers to helping, with some other words in this domain being kind, warm, generous, compassionate. Courage refers to the ability to tolerate distress, with some other words in this domain being resilient, tough, intrepid, and brave. Lastly, Holism may refer to the ability to integrate the other five virtues, transcend prior limitations, and connect as part of a larger socio-cultural, and even evolutionary and cosmological perspective. I suspect other words in this domain reflect the frequent social context or status of such endeavours, with words such as extroverted, vivacious, inspiring, and spirited.

Building a Stronger Culture

The Moral Landscape argues that we should build morality upon solid science. In this article I have provided a brief glimpse of how, suggesting attendance to six core values. Development of such values is associated with increased wellbeing and decreased physical and mental health problems, as demonstrated by many randomised placebo controlled clinical trials (the scientific gold standard) of psychological interventions. The evidence is good enough to begin applying scientific approaches to wellbeing on a larger cultural scale than is currently the case (Henriques, 2005; Seligman, 2011). Data collected on the way can be used to adjust and amend approaches, via evolutionary processes of cultural variation, selection and retention. This is temperate scientific progress, rather than hotly impulsive or coldly compulsive dogma.

At the conference I was asked about development of these values, and about the role of the golden rule (“consider yourself and treat others accordingly”, as stated by Confucius for example) – widely known as a culturally universal endorsement of altruism. As suggested by its position in the star, altruism is central to the development of other values through valuing the wellbeing of self and others. Mammalian brains do not self-assemble like those of many reptiles, but rely upon nurturance to reach their full potential (Hrdy, 2009). Altruism has ultimate origins in evolutionary processes such as kin selection (Hamilton, 1964) and (together with equality) reciprocal altruism (Trivers, 1971). Parallel to this, skeptical inquiry is a process fostering the accurate pattern recognition that characterises intelligence. Yet, as I said at the conference, altruism alone is as useless as a body without head or limbs, incapable of seeing wisely or acting effectively – and intelligence alone is as a head detached from body and limbs, potentially lost in autistic pattern seeking or psychopathy. And even head (I) and heart (A) are lame, without arming methodically for action (T), standing as two to exceed the power of one (E), stepping forward despite distress (C), and reaching forever higher to transcend what has gone before (H). Simplified even further – head and heart, standing together, standing strong, and reaching out to help.

We aim to build our most important cultural institutions upon solid science rather than superficial superstition. Our challenge is to speak comprehensively but comprehensibly and reach as many people as possible. At the conference, chemist Michael Edmonds spoke of our chemical origins in the heart of stars as “starstuff”, and biologist Alison Campbell of our biological origins in the great evolutionary tree of life. In this manner an evolutionary cosmology to which we all belong is now introduced at new entrant level in our schools, providing fertile ground for sustaining knowledge to grow.

In terms of physics we are matter and energy, creating and destroying, yet neither created nor destroyed. Awareness emerging, submerging and re-emerging, evolving as it is revolving. As a psychologist, I am aware that to grow starstuff into flourishing form, human genes need memetic light. Symbolic linguistic devices such as these words, the “Bright-Star” above or Humanist symbol below, are examples of memes that might aid the teaching of scientifically based morality and brighter prospects for individual and collective wellbeing.

“When will you attain this joy?

It will begin when you think for yourself,

When you truly take responsibility for your own life,

When you join the fellowship of all who have stood up as free individuals and said,

‘We are of the company of those who seek the true and the right, and live accordingly;

‘In our human world, in the short time we each have,

‘We see our duty to make and find something good for ourselves and our companions in the human predicament.’

Let us help one another, therefore; let us build the city together,

Where the best future might inhabit, and the true promise of humanity be realised at last.”

The Good Book 9:4-11(Grayling, 2011).

References

Ashton, M.C., Lee, K., & Goldberg, L.R.(2004).Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(5), 707-721.

Axelrod, R., & Hamilton, W.D.(1981).Science, 211,1390-1396.

Baschetti, R.(2007).Medical Hypotheses, 68, 4-8.

Blackmore, S.(1999).The Meme Machine.Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brinkmann, S.(2009).New Ideas in Psychology, 27, 1-17.

Dahlsgaard, K., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M.E.P.(2005).Review of General Psychology, 9(3), 203-213.

Dawkins, R.(2006).The Selfish Gene (30th Anniversary ed.).Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grayling, A.C.(2011).The Good Book: A secular bible.London: Bloomsbury.

Hamilton, W.D.(1964).Journal of Theoretical Biology, 7,1-52.

Harris, S.(2010).The Moral Landscape: How science can determine human values.New York: Free Press.

Henriques, G.(2003).Review of General Psychology 7(2), 150-182.

Henriques, G.R.(2005).Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61,121-139.

Hrdy, S.B.(2009).Mothers and Others: The evolutionary origins of mutual understanding.Cambridge, MA: Belknap/Harvard.

Kristjansson, K.(2010).Review of General Psychology, 14v4), 296-310.

Lee, K., & Ashton, M.C.(2008).Journal of Personality, 76(5), 1001-1054.

Paul, G.(2009).Evolutionary Psychology, 7(3), 398-441

Scott-Phillips, T.C., Dickins, T.E., & West, S.A.(2011).Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6(1),38-47.

Seitz, J.A.(2005).New Ideas in Psychology, 23,74-95.

Seligman, M.E.P.(2011).Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and wellbeing.New York: Free Press.

Trivers, R.l.(1971).Quarterly Review of Biology, 46,35-57.

Wilson, E.O.(1998).Consilience: The unity of knowledge.New York: Random House.

Winne, P.H., & Nesbit, J.C.(2010).Annual Review of Psychology, 61, 653-678.

Yamagata, S., Suzuki, A., Ando, J., Ono, Y., Kijima, N., Yoshimura, K., et al.(2006).Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 987-998.