Some claim our society is too materialistic and lacks spiritual values. But what would it be like to live in a society that rejects materialism?

Arnhem Land in tropical Australia has a curious status. Although the government has overall responsibility, the indigenous inhabitants are considered to be in control over the area where they live. Outsiders must seek permission to enter a tribal area and a permit is issued on payment of a fee. Twenty years ago the tourist fee was relatively modest, but for a mining concession the fee is substantial as one might expect. We paid $65 for two of us per day on our first visit, although fees have risen greatly over time.

Very few tourists visit because the fee is for entry only and there are no hotels, restaurants, shops or similar facilities. There are very few roads, or even tracks for four-wheel drive vehicles. However it is possible to fly in and stay at the small mining town of Nhulunbuy within Arnhem Land where there is accommodation, shops and restaurants. No permit is needed provided one stays within the town perimeter.

A tiny number of operators in Nhulunbuy will offer tours with a vehicle and guide, and assistance in obtaining the necessary permits. The tribespeople are generally not unfriendly but shy, and few will attempt much of a conversation even if they have sufficient English. As Australian citizens they are eligible for benefits so individuals have some income though very few have jobs (and those who do are nearly all women). A good deal of their income is spent on alcohol. Getting drunk is not frowned upon within the tribal system. Religion puts a high value on a trance-like state and it is not clear how inebriation differs from this (even to me). Violence when drunk can be punished, especially if somebody is harmed.

On one of our visits, a chief’s drunken son had just beaten a woman to death. A meeting of elders had decided that the spearing would take place immediately and that the official trial (that would presumably result in a conviction for manslaughter) would occur when he got out of hospital. On some previous occasions, the spearing took place when the offender got out of prison and this was thought to be unfair.

Some but not all children go to school. On one tiny island in the Gulf of Carpentaria I met a group of young boys living on their own to prepare for the ‘circumcision’ ceremony that would admit them to full tribal membership. They had spears and knives (but no clothes), and were living on fish and other seafood that they could catch or collect. Water was in short supply and the gifts of cold cans of soft drink were more than welcome. These boys (around 12 years old at my guess) could speak some English. But they could not reach a consensus as to how long they had been on the island, how long since they had seen an adult, how long they expected to stay or even whether they had ever been to school. I got the impression that they were not supposed to have any contact with me, but soft drinks overwhelmed any moral inhibitions.

Anthropologists have described this island sequestration of pre-initiates, but I doubt they interviewed the boys on an island. The written descriptions simply add to my scepticism of anthropologists. What I observed differed from the anthropological accounts in a number of important ways.

I have become friendly with one (white) Australian who had been initiated into one tribe and could act as interpreter. However my friendship has not progressed to the stage where I felt able to ask him if he had undergone the severe penile mutilation that the young boys are supposed to endure. The ceremony involves more than simple circumcision as understood by us.

On one trip my friend had recently taken a guy on an eco-tour. They first visited the tribe for permission and found a man apparently completing a painting on bark. In some parts of Australia paintings are made to sell to tourists but these are of variable quality. The tourist was excited at finding an authentic work of art, which he thought beautiful. The artist showed little reluctance to sell, and little interest in a price. But his work was not complete and he insisted it had to be finished. It was agreed that the tourist would return at the end of his visit.

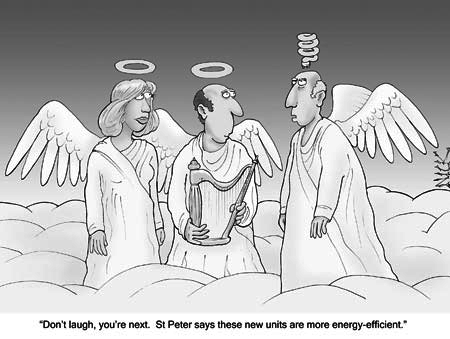

Some days later the guide and tourist returned and the artist produced his now-complete painting. It was nothing like the one that had been admired and the tourist did not like it. But, explained the artist, the one he had liked was still there, it was just underneath. In fact there were four layers of painting; none of these were intended to be viewed by human eyes. Painting is done to satisfy the artist and please the spirits who are not limited by human sense organs. The artist had some understanding that the tourist might wish to own something that pleased the spirits. He could not understand why the new owner might want to view the painting.

There are many rock paintings across the tropical North. However the access to some sites has been restricted or stopped altogether. This is not because the tribes think the paintings may be damaged by tourists, in fact they paint over some old examples. This does not ‘damage’ them as they are still there for the spirits. But viewing by non-initiates desecrates the site. Actually photography and video desecrates them even more but we were not aware of this on our earliest trips!

Most tribes are small; one we encountered consisted of about 40 individuals. All receive some assistance from the government and those whose lands contain valuable minerals get money from their leases. In fact the amounts from leases can be enormous when considered against the standard of the material possessions of the tribe, apart from its land.

A giant aluminium company built a village for one tiny tribe on the edge of a huge lagoon called Bradshaw Harbour. There were vast resources for fishing and gathering of food, but after a few years when the senior elder had died, the tribe abandoned their houses and moved to the edge of Nhulunbuy where they could camp within easy access to alcohol.

Of course there are outsiders with a mission to help the local people, medics, teachers, social workers and religious enthusiasts, but the curious status of the place allows the locals to determine what kind of help they will accept. These are tribal societies, so it is the elders, ie the older men, who decide.

Most outsiders would like to see the available money spent on material things like housing, hygiene, education, medicine, etc. That is, those things upon which our society puts great value. But the elders put the greatest value on their religion. This involves complex and lengthy ‘ceremonies’, when a tribe invites its neighbours to a session of feasting and ritual generally lasting many days. In earlier times this presumably had the practical result of reducing tension and the risk of intertribal war.

Initiated men are called ‘warriors’ in English translation, even though they may be young teenagers. I have been on a fishing/hunting trip with a ‘warrior’ whose grandmother told me was 13. He carried two spears and a ‘throwing stick’ (his term) sometimes called an atlatl or woomera by outsiders. However it was a sacred object, no uninitiated person could touch it or even learn its proper name and he did not know any other western names for the object.

We went fishing in one spot; part of our concession was to take along a tribal member. A woman agreed; she would spend her time gathering food on a sacred beach. But she wanted to also take her daughter who she thought had just become fertile. It was necessary also to take a warrior, because a girl not so accompanied would become pregnant by walking on this sacred beach. This had happened to her as a teenager so she was certain it was true. Our guide (in the woman’s hearing), explained that the tribespeople were perfectly aware of the connection between sex and pregnancy but they had sex all the time and pregnancy did not always result so some other factor must be involved. I decided this was similar to attitudes in rural Ireland where prayers to the Virgin are thought important in such matters.

Before money was introduced, the cost in resources of putting on a ceremony was considerable relative to the economic status of a tribe. However the number of people who could attend was limited to those tribes in the vicinity: within walking distance. Generally it is estimated most tribes held a ceremony only once a year, while they probably attended between two and four more, held by their neighbours.

Mining royalties mean that the tribes (though not the individual) have considerable discretionary income and a very large percentage of this is spent on travel costs, to allow the people to attend distant ceremonies and on catering for the greatly enlarged numbers who attend the local ceremony. If sufficient funds allow they may also increase the number of ceremonies held. These days food is purchased as well as gathered, in fact close to a supermarket in Nhulunbuy very little is gathered, while very large amounts of alcoholic drink will be needed.

At first the travel range was increased by four-wheel drive transport, but with unskilled drivers and a complete lack of mechanics for maintenance, these had only a brief useful life. Where mining roads have been installed, ground vehicles may still be of use, but road maintenance is costly and without upkeep no road is likely to survive even a single wet season.

Travel by air is more feasible and tribes now often hire air transport. This makes the whole of Arnhem Land within the range of any tribe living within one day’s walk of a bush airstrip.

Outside Arnhem Land, in Western Australia, taxpayers provide subsidy for tribal transport where there are no mining concessions. In 2007 we were at a small, isolated fishing camp (four anglers) in an uninhabited area when we had a visit from the ‘traditional owners’ plus social workers and government officials. They came supposedly to see that the region was being looked after properly. There is never any litter around at fishing camps in the Kimberley, so after this group had left one of the guides went round to pick up all the litter they had dropped – mainly cigarette butts.

There was no road access and no place for a landing strip. A helicopter was kept on the ground while the party was visiting. When it came time for them to leave it had developed a fault. Another chopper with a mechanic had to come to examine it, while a third very large machine came to pick up the party (they all had to travel at once instead of being ferried, as night was approaching). None of the visitors had been there before – it is actually Government land – ie public land and it could not support a permanent settlement now or in the recent past.

The main concern of the traditional owners was to ensure that tourist operators did not take people to visit ancient sites and in particular did not photograph, or even view, ancient rock art. Such visitors offended against the traditional spiritual values, but these people expressed no interest in charging fees to allow tourists to do these touristy things.

Further reading: Spoken Here: Travels Among Threatened Languages. M Abley, 2003. The Elements of the Aborigine Tradition. James G Cowan, 1992.