One of the perpetrators told the story behind the Grand Interplanetary Hoax of 1952 to the 1994 Skeptics’ Conference.

Hoaxes have probably been a part of life for thousands of years, ranging in scope, intent and outcome. Some such as the Piltdown saga veer out of control and have unforeseen and potentially serious consequences.

When Denis Dutton first asked me to give a paper on the great UFO hoax of 1952, I was somewhat coy about the matter. Subsequently I was tempted to accept, and here we are.

During the early 1900s, mysterious airships were sighted in various parts of the world, and New Zealand was no exception. While various psychological explanations have been forthcoming for the airship episodes, no evidence has surfaced to my knowledge concerning any structured direction to that piece of mystery history, although I have always believed a hoax might have been the initiating event. H.G. Wells’s haunting and sadly prophetic novel The War of the Worlds was available as a textbook to feed the imagination of the susceptible and the gullible.

We need to remember also that the Christian religion has always emphasised the Second Coming. Such teachings reinforce in successive generations the concept that there will be cataclysmic events and visitations, hopefully in one’s own lifetime. The factors which determine the life-cycle of these events are worthy of study. I have no doubt that many of them are the work of pranksters or elaborate hoaxsters, as is the case in the present episode.

Of more interest to people like me in describing something that happened before many readers were born or living in New Zealand is a retrospective analysis of the various participants, the perpetrators, the reactors and the bystanders. In my acceptance letter for this exposure, I said that I would couch my text, “in terms of what this particular episode teaches about young people’s attitude to pomposity in their elders and towards various aspects of the Establishment (in this instance represented by the Otago Daily Times)”.

A serious skeptic must be a serious historian with healthy respect for the broad picture, the fine detail, and also for what Denis has referred to as the partnership between History herself and Lady Luck.

I do not need to stress to this audience the fact that mythology soon surrounds events such as the “Grand Inter-planetary Hoax”, as the Knox College prank is now known in some circles. That mythology is largely concerned both with how the episode arose and with who was involved. I have chosen to tackle this topic in a chronological sequence, introducing analysis of events as I proceed. Such a plan makes it easier to strip away some of the mythology concerning the events of 42 years ago.

Knox College

During the 1950s, Knox College was a male domain occupied by young men from all over New Zealand, of varying ages, studying for a variety of professions. Within the college community were a number of ex-servicemen, most of them studying for the Presbyterian ministry. Knox had not been shaken at that stage by the liberalism of Lloyd Geering, but there were clearly defined groups within the “Div” students, as they were called, ranging from the more fundamentalist to those with what some perceived to be dangerously liberal theological points of view.

Amongst the medical students there was a similar range of believers, with the more traditional rigid group belonging to the Evangelical Union and the more daring, and I would say open-minded, belonging to the Student Christian Movement of which I happened to be President for part of the period we are discussing. At that time the Student Christian Movement quite openly accepted agnostics and others who were exploring and developing their concepts of themselves and the world in general.

Social life in the College centred on the supper parties which moved from room to room. Students became bored with swotting by about 9:00 or 9:30 and gathered together in various rooms and talked until midnight and beyond. The great strength of Knox College lay in those interchanges. These were much richer social gatherings than the somewhat rushed meals in the dining room. I remain very grateful to this phase of my student life, particularly for what I learned from people studying in the other faculties and from the ex-servicemen amongst us.

It needs to be remembered that the early 1950s saw the beginnings of what ultimately resulted in student unrest in a number of other countries and in the revolt of tertiary students against a number of manifestations of the old order. In my opinion, the stirrings began as students realised that a great new order had failed to emerge from the ashes of the Second World War. Rather, a potentially destructive conflict was emerging between what could crudely be called capitalism and Marxism.

Student Idealism

Throughout history, students have been aware of injustice and abuse of power by successive forms of the Establishment. Students have, to some extent, tended to divide themselves into those who put down their heads and acquire a qualification, looking neither to right nor left, versus those who gain pleasure and seek self-fulfilment in genuine attempts to improve, not only their own life, but that of others. While that may be jingoistic and simplistic it is highly relevant to the context.

During 1951 we had endured privation in the Otago winter during the waterfront and the coal miners’ strike. We had shivered in unheated rooms and endured a pretty awful diet amidst a so-called land of plenty. Regardless of the rights or wrongs of the Holland Government’s struggle with the wharfies and the miners, many of us in Otago became increasingly irritated by the sanctimonious attitude of the Otago Daily Times.

This is not mythology; the pompous simperings of the ODT were tackled regularly during capping week. At times the students set out deliberately to antagonise Mr Moffat and his “smug band of journalists and leader writers”. The Star was a ho-hum paper which did not excite nearly as much reaction on the part of the students. Undoubtedly there was much young arrogance behind our own attitudes, but also youthful energy, mixed with mischief and an altruistic outlook.

The idea of launching a major attack on the ODT surfaced in the winter term of 1952. The pre-occupation of the ODT with flying saucers, and the trivialisation of major events which were happening worldwide, was adding fuel to the antagonism felt among a range of students. What I shall term the “idealistic alliance” between many medical, dental, arts and divinity students provided a fertile area for the gestation of the hoax. From the beginning it was critical that a sufficient group of men with the necessary confidence in one another should come together if the venture was to succeed.

According to my records, the hoax idea was mooted vaguely for the first time in late September. Finally a group of five, at one particular supper party, concocted the crucial elements of the enterprise. One of the group had access to a secretary in the Medical School. She was the one significant person from outside the Knox confederacy who participated and maintained her silence over the years.

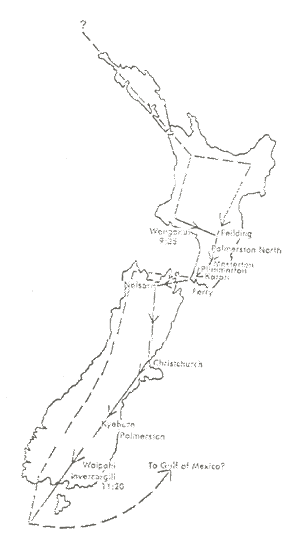

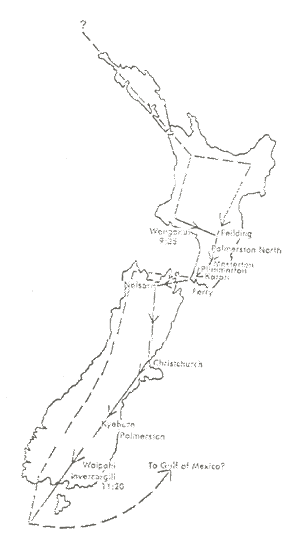

Final planning, however, was undertaken by a very small group which was a key to the outstanding success of the episode. For many years I kept a copy of the map I used to draw up the original plan. It was very similar to that shown on the construction produced by Brian MacKrell of Palmerston North in 1978.

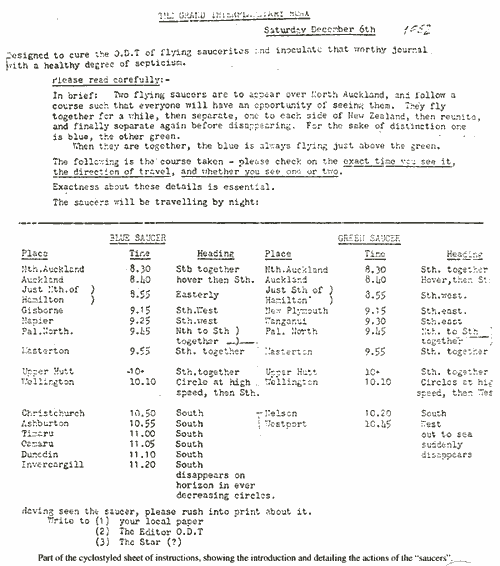

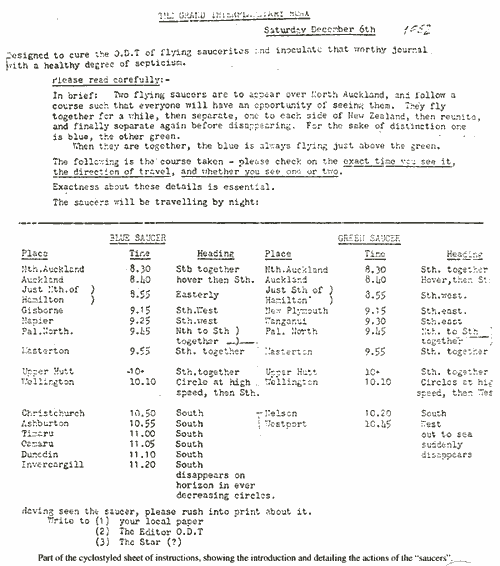

One document was central to the planning. The illustration confirms that at least some of the things I have said are not mythological. You will note that the single-page document starts off by defining the objective very clearly.

Designed to cure the ODT of Flying Saucerites and inoculate that worthy journal with a healthy degree of septicism [sic].

Spelling mistakes and the unconscious pun based on a spelling mistake, while not Freudian, are nevertheless interesting. We really only had one possibility of getting the typing done, and there was no proof-reading as far as I can recall. For “saucerites” read “sauceritis”, and for “septicism” read “scepticism”.

However, the point of the sentence is quite clear and an educationalist today would applaud the brevity and the irony inherent in that sentence. As you will note, it is a double irony.

The reasoning behind the genesis of two saucers, with different colour codes for the two extra-terrestrial objects, was itself based upon considerable discussion and simplification. There was much complexity during early stages of the planning with a tendency to various forms of hyperbole. All this was strenuously censored for sound reasons.

The blue saucer was to “disappear over the horizon in ever decreasing circles”. We did drag a few coat-tails!

The final paragraphs in the printed document are again an exemplary piece of the hoaxster’s art. Buried within these instructions are the fruits of our own research analysis of reports plus our own rudimentary understanding of the accoutrements of supersonic flight.

Once the document was available, it was distributed throughout the College, through the supper-party networking system. At this point, differing philosophies and personalities within the College became evident in the decisions taken as to who would and who would not take part. Two divinity students, in particular, protested that this was a dishonest exercise with which they could not associate themselves. They believed that the College would be brought into disrepute. Moreover, they were extremely disapproving of other divinity students who were prepared to indulge in such dishonest joviality. They raised a point which was again evident at the 25 year initial revelation. If we were prepared to dissemble to this extent as students, what were we going to be like in later life; what grip would we have on honesty and integrity? Most of us ignored such qualms, and it was notable that a number of ex-servicemen among the divinity students particularly relished their participation.

This was not the only major attack on the ODT by members of Knox College. A famous Resident Fellow, the late Don Anderson, who at one stage was on the staff at Massey University, found the ODT editorial policies particularly irritating and conducted an entirely fictitious correspondence during which he wrote letters for and against bagpipes over a prolonged period. That particular private pillorying of the august journal has never been revealed in public to my knowledge, but I stand to be corrected on that point. As far as I can recall, Don did not take part in this particular exercise but we would not have expected him to do so because he was grossly handicapped and easily identified. As a victim of cerebral palsy, his speech mannerisms were well known in Otago at that time.

There was one major risk involved in the planning which we had to accept. Everything had to be in place so that, as was the custom of those days, we could complete the bulk of our year’s study in the four to six weeks before the final examinations. This was the reason why the briefings and preparations of the instruction sheet occurred early in the third term. Also, various members of the College left at varying times over a total range of about six weeks. In turn the due date of December 6 was determined by the timing of the departure of the last students at the end of their examinations.

This lengthy delay between concluding the planning and the date of execution led to some awkward gaps in coverage of the country and to forgetfulness which I think was genuine on the part of some who had agreed to participate. Russell Cowie made strenuous and ingenious efforts to provide coverage from places in the South Island by preparing additional letters for the relevant areas. Some of the gaps were covered by correspondents stating that they had been travelling by car. This would account for a letter being posted at a distance from the alleged sighting.

To a perceptive reporter who took the trouble to collate the information, the fact that this was a spoof should have been obvious.

Pure Moonshine

One of my favourite pieces was the reporting of the sighting from Hokonui, the home of the famous southern moonshine whisky. The author of that letter had the sense not to sign himself McRae. I still find it incredible that the ODT did not pick up these trailings of the coat.

If I may be excused a modicum of parochialism I shall describe what happened in Auckland. I chose the Herald and rang from a phone box as I came off overtime, on a clear lovely evening. Fortunately the sky was clear over pretty much the whole of New Zealand on the night; this was the first piece of Lady Luck’s benevolence. Had Aotearoa lived up to its name, the whole scheme would have been strangled at birth.

The Herald reporter who received my telephone call was quite bland about it, asked for a name and address which I gave, having carefully selected a street in which the particular number did not exist (in accordance with the plan). I sent in a letter having said I would do so. Obviously no one ever checked up on that, or if they did they kept the observation to themselves.

A colleague from an adjacent wool-store was assigned the Auckland Star. This was a much tougher proposition. He gave a description which tallied with mine, as he walked home from a different wool-store and used a different telephone box. However, the Star reporter wanted a bit more than a name and address and John realised that this was a hazardous moment. However, he had a brilliant idea of saying, “If my wife knew I was out in this street at this time of night there would be all hell”. “No problem sir,” said the Star reporter and swallowed the whole thing hook, line and sinker. Another student used a similar device. Throughout the country people generally had no problems in having their stories accepted.

The Target Bites

The flood of reports obviously raised excitement. As predicted, the ODT gave quite unreasonable prominence to the reports while missing the whole point and not even correlating the North Island and South Island sightings. In its initial reporting it referred to South Island observations only, even though those in the North had been reported in the Northern press, with suitably modest prominence, and on radio.

At no stage did the biggest circulation newspaper of the country, the New Zealand Herald, or the Auckland Star give the story any undue prominence. The attitude of both the Herald and the Star implied that they thought there might be some trickery afoot. The Auckland Star ran a cartoon and a whimsical leader appeared in the New Zealand Herald. I should comment that the New Zealand Herald has always had a whimsical streak to it.

As many of you may know, there is a tradition on April 1 to publish very soberly written articles which are a send-up of this or that, perhaps the most famous one being of the description of the long-lost tunnel under Auckland Harbour excavated for military purposes in the 19th century. Huge numbers of citizens were taken in by that piece of writing. I am not sure whether Ted Reynolds was on the Herald staff in 1952 but the flying saucer leader incorporated the style of writing for which he was later to become notable, if anonymously.

We did have a problem in Auckland. A Canadian Pacific Airliner came over at the critical time and a group of cargo workers sighted something which was not part of our scheme. This was a further piece of intervention by Lady Luck however, because it tended to confuse things in the northern part of the country and it ultimately was quite useful.

Further south much ingenuity was exercised, including a report from one student and his son, (who certainly did not exist at that stage) reporting that they had seen the two discs together. About three days after the event, some newspapers had correlated all the sightings. The Carter Observatory, which had been contacted by more than one newspaper, had officially stated the reports had contained “quite worthwhile information”. The speed of the two objects had been calculated and tallied with our original computations.

“If only I had seen it” sighed Mr W.D. Anderson, a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society who was consulted by the ODT. “You cannot possibly ignore straightforward, intelligently written reports like these.” He added, “I cannot give explanations off-hand.” Meanwhile, dedicated saucer watchers had concluded that these “fully authenticated reports from New Zealand”, as they were described, indicated that “saucers were flying closer to the Earth’s surface”. This clearly heightened the interest and further raised excitement.

Front Page News

The ODT was in full cry, and 13 days after the event the front or main news page had a double-full-scale column headline entitled “Enigma of the Sky”. It was not the only major reference on the front page during that week. The ODT had commissioned a Mr Anderson and a Mr McGeorge to undertake a survey of the reports. These two worthy gentlemen concluded that:

Assuming that these reports of a swift-moving object in the sky on Saturday night are not the result of collaboration (and they appear to be genuine, independent observations) they constitute a surprising weight of evidence in favour of the proposition that some object of a bluish colour did pass down the South Island.

They went on to calculate size and height of the objects. They ended their report:

We are still looking forward to focusing a telescope on one of these mysterious objects. A telephone call ahead of the object would be helpful, and we suggest that any observer immediately telephone in reports to the nearest office to enable advice to send ahead in time.

A few late reports trickled in and this again was part of the original plan. These were heavily reinforced by Russell Cowie, which ensured that the ODT target was well and truly plastered. He wrote further letters to Southland and Wellington papers to ensure that the coordinated activities of the blue and green discs were recognised.

The excitement eventually died down. The Weekly News of July 12 1953 did feature an article entitled “Mysteries that Fly Past in the Night”, which was based on an interview with Mr H.A. Fulton, president of the Civilian Saucer Interrogation Society of New Zealand (CSINZ). He had been involved early by the ODT and other newspapers at the time of the hoax itself.

The Committee of the CSI had concluded that the most conclusive evidence of the existence of flying saucers was the series of reports received on December 6, 1952. He went on to state that the CSI was satisfied that all the natural and atmospheric explanation by scientists for the appearance of flying saucers did not promise a solution of the riddle.

“Time”, Mr Fulton said, “would tell and the time was not very far away.”

Unexpected Support

Lady Luck favoured us thrice. What we did not know at the time was that we had calculated the speed of our objects such that they would have appeared at the right time over the Gulf of Mexico where a B29 crew saw a small, unidentified flying object. In 1978 the report of that crew still remained on the US Air Force list of unexplained flying objects. The green disc which disappeared off Invercargill could have turned up along a great circle route to the Gulf of Mexico just in time to be observed by the American airmen in their B29. Others have carried out the same correlation which appears in one of the standard books on flying saucers. The New Zealand sighting of 1952 and the B29 report are frequently quoted as being the most convincing evidence to support the reality of UFOs.

In an account prepared in 1984 by Mason Stretch, then Secretary of the Knox College Students’ Club, and presented at an annual meeting of the Knox College Old Boys’ Association, the final two paragraphs ran:

Surely the ODT reporters, the main sub-editors even, must have purred when Mr Thompson of the Carter Observatory said to the ODT, “You have got times and you have got something which might give speeds…that appears to be worthwhile information.”

The ODT had nobly striven to assemble data and report to the public information of world shaking importance — so important indeed that what at other times would be major international news was squeezed out of the headlines by two saucy wee disks [sic] that hissed while hoaxers howled in the background.

I think we were all staggered by the success of the venture and were not quite sure what to do. There was a tacit agreement that nothing should be said. We had achieved our objective, felt satisfied and, quite frankly, the ODT continued on in its ponderous manner. Capping came along next term and, predictably, the memory of the events receded into the background. As I have indicated there were some periodic reports of the 1952 excerpts in the press including the Weekly News article. Some who participated in the hoax did begin to feel a little uneasy that some people 10, 15 and 25 years later were still taking the thing far too seriously, just as the 1909 airship episode with slow moving dirigibles steam-powered from Dargaville to Invercargill towards subsequent sightings in Australia had never been explained. It seemed reasonable to leave things for a while, but not forever.

In the Christchurch Press of 4 March 1978, Brian MacKrell of Palmerston North published an article headlined “The Night of the Hissing Discs”. He had earlier analysed the 1952 newspaper reports and his work produced the map referred to earlier. He said he was not a member of any organisation which believed in UFOs but he had collected newspaper reports of the sightings as a child. He had linked up the B29 bomber report from the Gulf of Mexico. He was aware of the 1909 airship reports.

With what appears to have been unconscious irony, the ODT republished the MacKrell article one week later. There is no indication that the ODT had any inkling of its role as the prime target in 1952.

Some of the group of now moderately old Knox men decided enough was enough, and Ken Nichol of Christchurch Teachers’ College revealed to the Press a general outline of the hoax. As far as I can tell the ODT never published Ken’s article.

As we expected, the reaction to the Ken Nichol revelation was mixed. Some letters refused to accept that the hoax was a hoax.

I believe it is clear from the editorial in the New Zealand Herald and the cartoon in the Auckland Star that the northern papers regarded the whole affair as entertaining and amusing. I suspect in retrospect that they might even have guessed that the ODT was the target. Certainly, when one looks at the New Zealand Herald over the relevant time, international news was not displaced off the front page in the Auckland papers as it was in the Otago Daily Times.

In terms of its basic purpose, the hoax was designed to make the ODT look foolish, mainly in the eyes of those who perpetrated the hoax itself, and hopefully to others. The low standard of professionalism shown by the newspaper reporters and sub-editors in terms of their analysis of Press Association reports, their failure to undertake some simple correlations, and their failure to pick-up the clues deliberately pointing to this being a hoax, almost certainly had no impact within the paper itself and probably not amongst a majority of worthy readers in Otago.

Hoaxers Satisfied

To those of us who took part in the hoax, there was a buzz of excitement and gratification. Our suspicion that the Fourth Estate could be manipulated, even by amateurs, was confirmed as were our thoughts concerning what determined some major aspect of newspaper policy. In a city that had prided itself as the intellectual centre of the country, the toes and part of the fore-foot of the main newspaper were revealed to us as objects of clay.

While we were poking fun at one major pillar of the Otago establishment, we were also indulging in the freedom offered by that academic environment and by New Zealand generally. Like the Oxford students who dug up part of Oxford or Regent Street and got away with it for something like a week, we had risked creating a nuisance of ourselves at the same time as we had challenged pomposity and credulity. We were mounting what we believed to be a humorous but constructive protest against what we correctly perceived to be the destructive nature of modern day superstition and witchcraft, and their handmaidens in some sections of the media.

Ours was a one-off exercise unlike the much more elaborate campaign undertaken in the seventies and eighties by the crop circle hoaxers. Bower and Chorley were in their fifties when they concocted their crop circle hoax as a joke, once again based upon a flying saucer motive. They also were staggered at their success and instead of confessing to newspapers, they made use of the original scheme to spell out the words “we are not alone” in 1986, and “copycats” in 1990. Once again, however, the believers took over and the huge geometrical precision of the July 1990 hoax convinced UFO Research Groups and the United Believers in Intelligence, that intelligence beyond any earthbound being had created the nine circle Worcestershire patterns.

Those particular episodes are much more complex than our own efforts, and just who is hoaxing whom remains unclear. At times it seems clear that the crop circle series may even have been maintained in the interest of some journalists, cynical or otherwise.

History does repeat itself in the arena of hoaxism and Lady Luck rides side-saddle e’en to the noo.

At least some who reacted to Ken Nichol’s preliminary confession believed that the Knox College students had betrayed their academic standards and had displayed a shocking lack of integrity. How could we be trusted on any stage thereafter? The argument that young radicals later became conservatives did not hold much weight with these stern critics. I believe that such guardians of absolute truth failed to perceive that we were acting out of a very healthy intellectual approach to life in general.

Moreover, from what I know of the subsequent lives of a moderately large number of the group concerned, they have maintained a sense of proportion during their careers and they have neither become cynics nor carping critics. Maybe it is their sense of humour combined with their serious intent and a critical capacity to analyse complex issues which has maintained in them this balanced perspective which is a key element in professional success.

I feel there is ironic justice perceptible in the fact that Russell Cowie is an acknowledged expert in the area of the nature and use of historical evidence. I hope that young people continue to behave in the way we did, particularly if they maintain into later adult life a sense of fun, a sense of proportion and an approach to the Establishment which is responsible on the one hand, but skeptical and critical on the other.

And so I conclude and leave you to your own interpretations of one of the cataclysmic events which brought to an end anno domini 1952.